From Direct Lending Funds to the Capital markets?

![]() Private Credit Middle-Market Opportunities in Europe (PDF version)

Private Credit Middle-Market Opportunities in Europe (PDF version)

Executive Summary

This commentary explores the market for lending to middle-market corporates in Europe, with the ultimate aim of understanding the investment opportunities in this respect. Middle- market credit has emerged in recent years as a distinct asset class in Europe, but for now is largely manifest in private credit direct lending (unlisted) funds. We see potential for such opportunities to spill-over into the tradable capital markets before long, as we touch upon below.

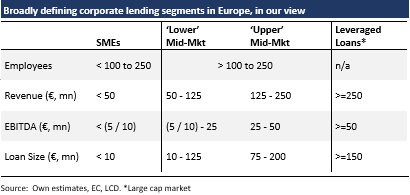

Private credit, or direct lending more specifically, is a post-crisis phenomenon that coincided with bank lending retrenchment in Europe given capital/ leverage constraints and more conservative risk appetites. The term ‘private credit’ tends to be a catch-all for lending to companies, covering senior to subordinated /PIK to distressed financing. Within this, “direct lending” is generally seen as the more vanilla lending strategy, often branded as senior loans to middle market borrowers. For the purposes of the proceeding discussion, we would broadly define middle-market companies as firms with earnings of between €15mn and €50mn as the upper-most boundary, with debt ranging up to €250mn.

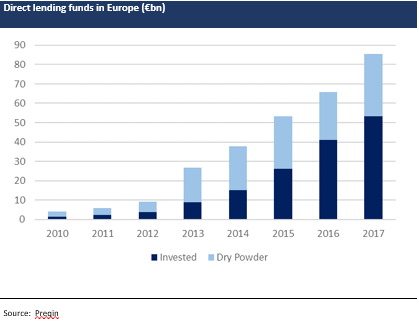

Institutional money inflows into European private credit direct lending funds has looked relentless in recent years, with total AuM among such funds estimated at €100bn+ currently. Yet the share of institutional funds versus banks in the overall corporate credit economy is still very small in Europe (less than 3% on our estimates), although such funds appear to be capturing an appreciably greater share of new loan flow. On this observation alone – and considering the extent of institutionalisation in the more mature US corporate credit economy (non-bank penetration estimated up to 60%) – this direct lending ‘revolution’ appears to have a long way to run before being exhausted.

But in our view, the direct lending model faces certain challenges in building a lasting footprint in the European corporate credit economy, key among which include:

- Deploying AuM into more diversified loan markets. Direct lenders have been able to compete based on their ability to underwrite more complex or ‘off-the-run’ credit relative to banks, but evidence points to both origination bottlenecks generally (highlighted by the extent of fund ‘dry power’, not least) and lending concentrations into sponsored and/or larger-ticket syndicated loans. (Indeed, mid-market non-bank lending seems largely an import of leveraged loan market practices). Establishing deployable origination niches away from what seems like a crowded market in lending to such companies, and into more mainstream borrower segments, would better anchor the long-term viability of the direct lending model, at least in our view

- Loan credit management, particularly under any cyclical stresses to come. Notwithstanding the generally superior credit performance of mid-market loans versus large cap equivalents in the recent past, the real test for this young alternative lending sector is of course still to come. Against the backdrop of unparalleled investment inflows and likely origination deployment pressures over recent years, we feel there are legitimate concerns around lending discipline, adverse selection and vulnerabilities to idiosyncratic events, risks which should become more transparent in any credit recession going forward. The workout capabilities of direct lenders have also yet to be fully authenticated, noting the benign credit cycle hitherto.

In building a resilient private credit model that outlives the current ‘bubble’ and any cyclical correction to come, we would surmise that direct lenders will need to replicate to some degree the origination and credit management infrastructure of the bank lending system in Europe. Doing so is tantamount to becoming ‘owners’ of credit rather than traders/ managers. Navigating such challenges successfully should create a more permanent, meaningful footprint for such alternative lending models in the European credit economy, where bank disintermediation opportunities generally remain compelling. (To be sure, direct lending funds in middle-market credit have little by way of non-bank lending competition in Europe currently). From where we are today, raising fresh capital to drive such institutionalisation seems the least of the challenges ahead.

As the institutionalisation of the middle-market credit system in Europe matures further, we expect capital market opportunities to emerge as alternatives to investing in unlisted direct lending funds. (Tradable markets are already established in SME credit and leveraged loans, either side of the middle-market lending spectrum). We see the development of such capital markets being fuelled by demand from direct lending funds for alternative channels of permanent capital (via public equity listings) and/or alternative sources of leverage (via CLOs namely), trends that have driven deep capital markets for middle-market lending in the US. Absent any credit cycle shocks over the foreseeable future, the tempting risk/ return profiles of middle-market private credit should also lend to this capital market growth.

Scoping the opportunity set in Europe

Notwithstanding the fact that middle-market direct lending is for now by-and-large an import of lending technology that is established in the large cap leveraged loan sector, the capital market or tradable footprint for such opportunities remains distinctly in its infancy, in sharp contrast to the institutionalised large cap market which is visibly represented both directly and indirectly via the established CLO market as well as a relatively deep market for listed loan funds.

Indeed, if we were to isolate middle-market direct lending opportunities, to our knowledge there are no listed funds in Europe at this stage. Moreover, there are no pure middle-market CLOs in Europe either, as yet, though a few deals have portfolios with not insignificant portions of mid-market loans. (A recent example of such a transaction is PGIM’s Dryden 63). And even further afield in the market for capital relief transactions related to bank-originated mid-market loans, we know of just one CRT trade – the Lloyds Cheltenham deal from end-2017 – that is based on credit protection of a mostly middle-market corporate book. (To our knowledge, four other bank CRT trades have come with a mix of SMEs and mid-market loans).

The largely unlisted nature of mid-market credit opportunities in Europe – certainly in the case of opportunities related to non-bank direct lenders – is somewhat puzzling considering the scale of investor appetite for such opportunities currently, manifest in the rapidly growing footprint of (unlisted) direct lending funds in Europe. The lack of capital market opportunities stands in distinct contrast to other segments of corporate lending in Europe, namely SMEs (represented via ABS and listed equity funds as well as P2P platforms) and large cap lending (syndicated tradable loans, listed equity funds and CLOs). Europe also differs noticeably to the US in that respect. Tradable formats of US middle-market lending include the likes of the now-established BDC (Business Development Companies) market as well as other listed vehicles such as retail funds. Moreover, the middle-market sector is a defined sub-asset class within the US CLO universe, witnessing nearly $30b in primary volumes over 2018. This capital market opportunity set in the US is poised to grow further with BDCs recently permitted to lever up to 2x (as opposed to a 1x ceiling before) while also being allowed to issue CLOs as a tool for such gearing, following the recent SEC no-action letter on risk retention. (The risk retention rules were rescinded for “open market”, large cap CLOs early in 2018 but mid-market CLOs, and sponsors such as BDCs, were still deemed to be subject until recently).

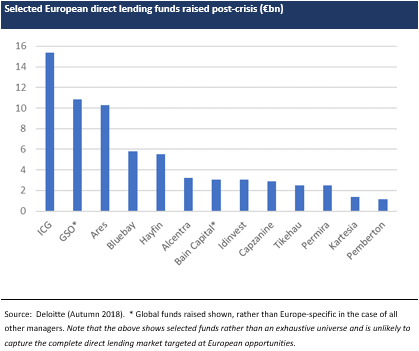

As we also reflect in the outlook section below, we think the European middle-market credit opportunity will spill-over into the capital markets before long. But for now, investor access to such opportunities is limited mostly to unlisted private credit funds. We would note that the biggest funds still dominate the overall market, with a relatively long ‘tail’ of smaller, often more specialised, funds. Counting among the more dominant mangers of European unlisted direct lending funds are firms such as ICG, Ares, Hayfin, BlueBay and Alcentra, with the likes of Pemberton, Permira and Tikehau also emerging more recently with sizable direct lending strategies.

At this juncture we would make the notable observation that the pre-crisis era offered more capital market opportunities in the mid-market space in Europe, namely via highly esoteric CLOs. Germany, in particular, witnessed a number of originate-to-distribute platforms (a few of which were bank-sponsored) where lending activities were focussed on mid-market corporates. But in sharp contrast with direct lending funds today, such platforms were engaged in hybrid/ mezzanine or ‘profit-participation’ lending strategies, offering corporates tax-friendly, enhanced leverage versus what was available from the banking system, or indeed to corporates without access to banking credit at all. In the event the asset class did not survive the 2008 crisis, nor did most lending platforms. Defaults significantly exceeded original expectations, driven by the degree of adverse selection coupled with excessive gearing. At its peak, such mid-market CLOs totalled more than €5bn.

Exploring the risk/return profiles

Analysing the risk/ return characteristics of the middle-market corporate credit opportunity in Europe at this stage is more art than science, given the lack of transparency in the absence of any authentic capital market activity. Unlisted funds do not systematically report returns – nor indeed any measure of risk exposures – as part of their normal course of business. Still, we feel there is sufficient data (observed or anecdotal) available to generally size the risk/ return profile of the European middle-market opportunity.

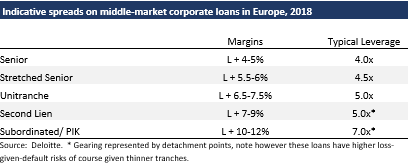

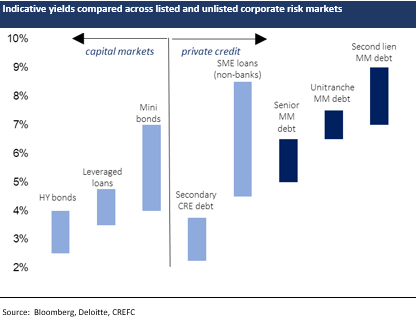

According to data from Deloitte, European mid-market loans yields range from ca. L+5%-6% for senior secured to ca. 7% for unitranche facilities and up to 10+% for junior, equity-like exposures. (All observations herein are based on data published prior to the year-end credit market sell-off). Generally, non-bank originated mid-market loans in Europe appear to yield more generously than larger cap leveraged loans (L+3.5%-4% in normal periods, typically). And to the extent observable, middle-market loan yields are superior to equivalents in most European private placement markets, certainly in the case of the mature, established sectors like Germany’s Schuldscheine market. By way of headline comparisons, US mid-market loan sector yields average approx. 6%-7% as at Q3 2018 (Source: Thompson Reuters), have traded in a relatively stable range over the past few years.

The relative value of alternative mid-market loans versus comparable credits in the traded market is therefore plainly visible in headline spread differentials. (By comparable credits we mean sub-investment grade paper). Yield premiums to broadly syndicated leveraged loans typically average ca. 200bps (similar to the US), with this differential appreciably greater (ca. 300-350bps) compared to traded high yield BB-rated bonds. However, we would caution against over-emphasising the yield pick-up in this regard, simply because mid-market loans in Europe are at this stage inherently illiquid compared to syndicated leveraged loans and of course the high yield bond market. (In other words, the yield premium could arguably be justified as an illiquidity premium). As a case in point, mid-market loan yields are seemingly no more generous than margins normally observed in the smaller SME segment, where non-bank secured loans can yield up to 6%-7%.

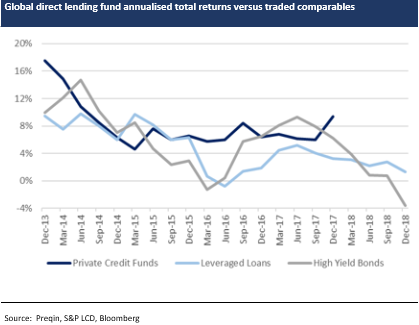

Returns on direct lending funds currently provide the only performance yardstick for middle-market credit opportunities in Europe, in the absence of any observable capital market alternatives. For the purposes of understanding such fund returns, we refer to data provided by Preqin as well as fund IRRs reported by Bloomberg. According to data from Preqin covering all direct lending funds globally, net total returns have ranged between 6% and 9% annually since 2014, prior to which returns – in what was a smaller, disparate market for such funds – were noticeably higher (reflecting higher loan yields not least), typically in the 10-20% region. Our analysis of Bloomberg data, isolating direct lending funds in Europe, show reported IRRs broadly in the same ball-park since 2014 (i.e., 6-9%). In any case, these anecdotal data clearly evidence that mid-market direct lending opportunities in Europe have, to-date at least, delivered returns that look to be superior to most comparable traded debt markets, arguably also outperforming from a risk/ return perspective noting the more volatile public markets. While fund returns hitherto have commonly been paraded as being uncorrelated to traded risk assets, we feel the relatively short life of such funds has not provided any meaningful opportunity to demonstrate the true extent of any performance linkages just yet.

Our analysis of Bloomberg fund IRR data highlights a notable dispersion of reported returns. To make our point, we note that the IRRs among such funds in Europe averaged around 6%-6.5% annually in 2016/17, but with a standard deviation of 7% over the two-year period. In cases of funds posting above-market returns recently (or alternatively, returns not commensurate with mid-market par loan yield carry), we believe the incremental returns are likely attributable to one or more of the following factors – an overweight of riskier or ‘special situation’ (including potentially distressed) assets, the inclusion of fee income including origination fees which can range up to 2-3% and/ or fund gearing of course. Leverage is employed by nearly half of all funds (40% in Europe, according to the 2018 survey by the Alternative Credit Council (ACC)), with gearing normally limited to 2x. Based on market feedback, we understand such leverage facilities tends to be longer-term in tenors, limiting any maturity transformation risks at the fund level.

Judging credit performance for such strategies is also a somewhat nuanced process given the lack of transparency. To be sure, mid-market corporate defaults and losses thus far have been low in Europe, helped by the benign credit cycle in recent years.

Using rating agency data and analysis of leverage finance related to borrowers with total debt <€200mn as a proxy for the ‘mid-market’ corporate economy in Europe, most viewpoints generally underline the better credit quality of this segment of the loan market relative to larger cap borrowers, whether quantified by lower total leverage or greater equity cushions or other more conservative credit metrics. Moreover, origination practices are widely thought to have been more lender-friendly in the smaller cap loan space, manifesting generally in better covenant protections than seen in the larger cap syndicated market in recent years. Fewer lenders to each borrower – or bilateral lending in some cases – looks to have also lent to more expedient credit management (amendment agreements and so on), delivering better credit performance relative to the mainstream leveraged loan market. And given higher loan yields, the spread per turn of total leverage has also therefore been generally superior to the leverage loan market, but we would again caveat this observation by noting that liquidity – as a separate measure of risk – is also significantly less in mid-market loans.

According to data from Fitch, smaller (<€200mn) loan default rates have almost consistently been lower than larger leveraged loans since 2011 in Europe (falling to zero in 2015 and 2016), with seemingly the only outlier being the spike in 2017 on account of just two defaults. Data on the deeper US market evidences this trend in a more concrete manner. In the ten years to end 2017, the average annual mid-market default rate in US was 1.9% vs 2.8% in large cap high yield loan market (source: Fitch). Equally, in the more recent five-year period (2012-17), the average default rate was 1.5% in the mid-market segment vs 1.9% in large caps.

The above considerations regardless, we take a more cautious view on trends going forward in the mid-market credit space. Low historical default rates have undoubtedly benefited from the bullish credit tailwinds of recent years, not to mention flattered by the typically longer-term bullet maturities of such loans. We feel the real test for this young alternative lending sector is still to come, and would highlight the following points as potential sources of credit vulnerabilities in any next cyclical downturn:-

- Better loan credit metrics versus large cap leveraged loan norms overlooks the fact that middle market borrowers are often inherently riskier credit propositions given their relative lack of operating scale and funding resilience. Fitch, for instance, assigns credit estimates consistent with lower sub-investment grade ratings for the majority (>95% in Europe) of smaller borrowers in the leveraged loan universe, precisely for these reasons. The prevalence of bullet loan maturities adds refinancing liquidity (‘cliff’) risks to the mix

- Retrospective observations of more conservative loan qualities in the mid-market space versus the larger cap market may also not accurately reflect contemporary lending practices. We think it reasonable to assume that there has been some ‘creep’ of looser leveraged loan lending styles into the mid-market direct lending space. (According to LCD, up to 80% of leveraged loans underwritten in H1 2018 were considered covenant-lite). To be sure, the amount of money flowing into this particular debt strategy would normally predicate more borrower-friendly lending

- The dominance of sponsored deals in the asset allocation of some funds should also be considered in this respect. While sponsored loans on the one hand have certain advantages such as the ‘socialisation’ of risk underwriting and more layered due diligence on borrowers, the flip side of this on the other hand is more borrower-friendly loan structures (whether measured by degree of gearing or covenant protections) and potentially weaker alignment of equity interests ultimately. Moody’s have cited that private equity sponsored companies tend to have higher default risks than their non-sponsored counterparts, all else being equal

- As with any alternative finance model, adverse selection is a key risk consideration in our view, particularly of course given that funds typically target borrowers who are unable to access bank credit. We should caveat that the lack of bank financing for such borrowers may be for reasons other than credit-worthiness (to include duration or other non-credit complexities), yet adverse selection remains a natural concern to us given the backdrop of heavy fund inflows coupled with deployment pressures

- From a portfolio perspective, middle-market credit portfolios are likely to be characterised by greater concentrations – whether by name or sector – than large cap leveraged loan portfolios, reflecting their lack of market depth. Such portfolios may therefore be incrementally vulnerable to idiosyncratic credit events. (To illustrate this risk, we note that in 2017 – according to Fitch – leveraged loans sized <€200m saw defaults jump to above 3% from zero in the prior two years, on account of just two defaults in the retail sector). We see this lack of diversification being arguably a reason why mid-market CLOs in Europe have not emerged as yet, that is, such loan pools are likely ‘unsecuritizable’ given credit lumpiness, being better suited to fund rather than securitization structures. Potential borrower overlap across the direct lender fund universe may further serve to exaggerate any idiosyncratic default shocks

- The sufficiency of restructuring/ workout capabilities within the operating models of direct lending funds is still to be fully explored, considering what has been an untesting credit cycle since this industry emerged in post-crisis Europe. Private credit manager resources look to have been disproportionately focussed on origination efforts thus far. On the premise that the industry experiences a credit cycle correction in due course, and further given that middle-market loans in Europe do not benefit from any meaningful secondary liquidity, we see borrower workout capabilities as one of the key factors distinguishing fund performance ultimately.

At the risk of stating the obvious, we remark finally that private mid-market credit fund total returns will of course be heavily dependent on loan payoffs more than anything else ultimately, not dissimilar to the economics of other par loan trades. Borrower default behaviour, rather than yield carry, is therefore key to fund performance over the next cycle, which we think will provide the first credible opportunity to judge the asset selection and credit management qualities of direct lenders. The more mature US mid-market corporate economy has recently witnessed some signs of credit stresses (albeit idiosyncratic rather than systemic at this stage), which has impacted price action in the BDC sector.

The outlook from here

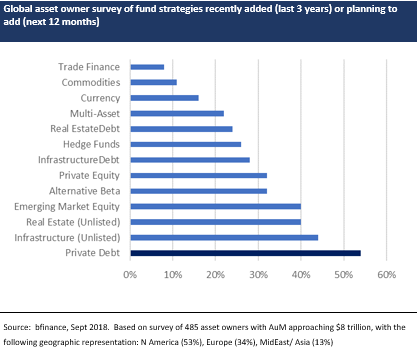

In our view at least, the breakneck pace of growth in the private credit direct lending market in Europe since 2013/14 in an omen for both the potential fortunes as well as challenges for the sector over the foreseeable future. Whatever anecdotal evidence there is largely suggests that the end-money appetite for such alternative debt strategies remains strong (bordering on insatiable), with direct lending often cited in most institutional surveys as the most favoured opportunity within the overall private credit market. Indeed, measured by the quantum of recent inflows, the private credit/ direct lending market already feels ‘over-bought’ to us, considering what is still a young and untested opportunity.

Whether or not the heavy supply of fresh direct lending funds in recent years outweighed the natural financing demand from the mid-market, translating therefore into easy credit for end borrowers, will become clearer under any credit cycle correction to come. Any fundamental credit recession – or equally a prolonged credit liquidity dislocation – will also likely test the hypothesis that direct lending strategies provide for uncorrelated, above-market returns. We expect any such headwinds to temper the rate of fund inflows, or at the very least lead to more selective allocations of such money. At this point we would add that any rate tightening cycle, if taken in isolation, should not in itself pose material risk to asset valuations given the predominantly floating-rate nature of loans.

All that said, while the defensiveness of direct lender middle-market portfolios will of course be tested in the next downturn, we sense that the industry is sufficiently deep-rooted to survive any such stresses. In other words, we feel that private non-bank credit is more a structural ‘revolution’ in the corporate credit economy that is premised on lasting financing gaps in bank lending, rather than an opportunistic ‘trade’ that is critically vulnerable to being unwound. (To this end we would point to the private equity industry, in which the explosive growth during the 2000s was often deemed – wholly inaccurately – by many commentators as unviable. We would also single out the enduring institutionalisation of the US lending market triggered by disintermediation opportunities in the aftermath of the early 1990s S&L crisis). In our opinion, the European credit economy will likely witness deeper alternative lending markets going forward, guided not least by continued bank disintermediation opportunities on the one hand and policy maker efforts to cultivate non-bank lending on the other (the CMU is a notable initiative in this respect). Direct lending funds appear well placed over the cycle to continue exploiting this trend. Unlike in the US, there is for now little non-bank competition for direct lenders within the middle-market credit space in Europe.

But further entrenching the direct lending model in Europe is not without its hurdles, in our view. We would describe the key challenge going forward as being able to replicate to some degree the infrastructure of the bank lending system in Europe. By this we mean the ability to deploy institutional inflows into more mainstream borrowers (away from the crowded sponsored/ syndicated capital markets) and to establish workout capabilities akin to being credit owners (rather than credit ‘traders’). To this end we believe private credit funds will need to invest in both origination and credit management infrastructure in order to demonstrate resilience of the direct lending model over cycles. Doing so will help secure a more unassailable position for such lenders in the credit system, at least in our view.

As the institutionalisation of the middle-market credit system in Europe matures further, we see capital market opportunities emerging as alternatives to (locked-up) investing in unlisted direct lending funds. Middle-market managed CLOs sponsored by such funds look poised to make their debut in Europe before long, particularly with better depth and diversity to the underlying asset market. (To be sure, the adequacy of middle-market loan yields already makes this asset class CLO-friendly). We expect such CLOs to be complemented potentially also by securitisations of investment bank leverage facilities to private credit funds. Away from asset-backed debt, we anticipate more by way of tradable equity opportunities in middle-market loan funds also, shadowing similar public listings seen in related alternative finance sectors such as large cap leveraged loans and SME lending (P2P-sponsored especially). Any BDC-equivalent legislation in Europe – whether under the auspices of CMU or otherwise – would of course be radically transformative in terms of capital market opportunities, but at this stage we do not foresee any such sweeping regulatory changes to the lending system in Europe.

Appendix

Defining the middle-market institutional lending opportunity in Europe

In Europe, SMEs are defined in official literature while large caps are de facto defined (historically) by its institutional capital market ‘cut-off’ within the corporate lending spectrum. Middle-market corporates have lacked similar defining characteristics for the most part. For the purposes of this discussion, we would broadly define middle- market companies – by process of elimination more than anything else – as firms with revenue between €50m and up to €250m as the upper-most boundary, and EBITDA between €15m and €50m with debt ranging from say €10m to €200m. Derived from various official sources, we roughly calculate that in the EU4 (UK, Germany, France and Italy), the middle-market corporate economy accounts for around a third of GDP and labour force participation, in this regard broadly comparable to the proportionate footprint of the US mid-market.

We estimate the total market of such mid-market lending in Europe to be in the ca. €3-3.5trn range (this includes real estate and other asset-based lending), which we calculated based again on total corporate lending less the lending stock in the SME and large cap segments of the market. Of this amount, we estimate direct lenders account for ca. €80-90b, based on data on funds raised and deployed thus far in the middle market space. If our estimates above are ball-park correct, then direct lenders have a ca 3% market share of the total stock of lending to the middle market in Europe, or modestly higher if isolating loans ex real estate. But on a flow basis, we believe direct lenders enjoy up to a ca. 10% market share currently based on the same calculations.

By way of comparison, the US middle-market economy occupied by direct lending funds is moderately larger at around $120bn (deployed and uninvested combined), according to Preqin. But taken together with the remaining broad depth of the non-bank lender universe to incl BDCs, CLOs and other institutional lenders including retail funds, the extent of bank disintermediation is far greater than in Europe, with estimates typically ranging from 40% to 60%. To be sure, banks share of the US large cap leveraged loan market is less than 10% (source: LCD) reflecting the scale of institutionalisation over the past 20 years or so.

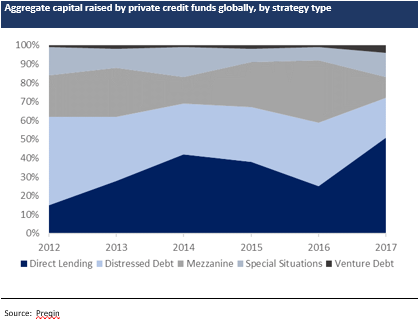

We feel it’s worth also making the point that ‘private credit’ tends to encompass all types of specialised/ borrower-specific lending, from vanilla lending to structured to infrastructure/ real estate etc. In the US at least, such direct lending strategies generally started with mid-market lending but has since expanded to include many other forms of financing and borrower types. In Europe direct lenders can have various (often overlaying) strategies from direct mid-market/ large cap senior lending to mezzanine to distressed / special situations, aside from sector specialisation such as real estate or trade/ receivable financing – indeed, many of the more established managers in Europe started off as specialists in the loan markets before broadening their product suites to include other forms of direct lending. As far as we can tell, there seems nothing formulaic connecting direct lending to middle-market credit, with the brand still somewhat loosely defined. For instance, It is still common for direct lending funds to allow buckets for special situation / distressed opportunities.

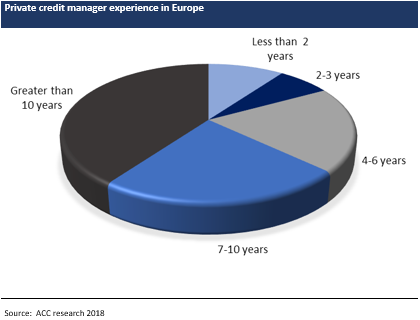

Private credit AuM as a whole has witnessed annual compound growth of 20%+ in the post-crisis era, with total AuM globally on track to surpass $1 trillion by 2020, according to forecasts by the Alternative Credit Council (ACC). Direct lending is the most dominant strategy among private credit funds, in terms of capital raised/ deployed. According to Deloitte, direct lending funds raised $82.7b in Europe since 2013. (Ares alone raised €6.5b in the largest European direct lending fundraise ever in 2018). Preqin data points to $39bn of dry powder currently among direct lender funds targeting Europe, with over $130bn raised in Europe since 2008 (via 160 funds). Many newer direct lending managers have emerged in recent years, with the industry catalysed by the significant money flows into such strategies – less than half of private credit managers have been in the market since the pre-crisis era, with 10% of managers in Europe operating the market for less than 2 years, according to ACC research.

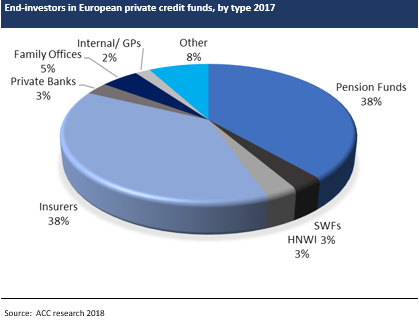

The end money for such strategies comes from global asset owners for the most part. Pension funds are understood to be the largest source of money for such opportunities, with family offices making up the smallest segment at 5%, according to the ACC. Regionally, North America institutional money dominates (38%), followed by Europe (31%, mainly insurance money). All said, direct lenders look to have become established as a favoured alternative investment class for many asset owners.

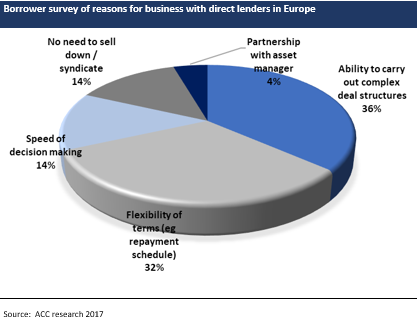

Like in other alternative or speciality non-bank lending in Europe, the competitive advantage of private credit managers is their ability to underwrite complex, off-the-run risks relative to the more conservatively constrained underwriting style of bank lenders. This typically manifests in lending features such as higher gearing and more flexible terms (including undrawn commitments, which is particularly capital expensive for banks nowadays). Aside from sourcing, credit underwriting is generally considered among the more demanding/ intensive aspects of direct lending in Europe, in turn underlining the appeal of sponsored deals where borrower credit intelligence tends to be more readily available.

According to ACC, 40% of direct lender funds globally are targeted at small balance loans/ SMEs, loosely defined as such. A further 20% comprises lending to large cap borrowers. Following on, one could crudely assume this data as implying that up to around 40% of direct lender funds are accounted for by mid-market corporate borrowers, again loosely defined. Judging by what data and intelligence there is on loan sizes as well as selected borrower/ loan transactions showcased by managers, it would seem to us that some – or indeed most – direct lenders in Europe tend to crowd into the upper segment of the mid-market, where sponsored deal flow is more dominant. (Syndicated lending formats via the capital market can also feature in the larger ticket mid-market space, however such lending remains small in Europe relative to the US). We see this segment as the ‘lowest hanging fruit’ in terms of deployable opportunities for direct lending funds, a segment where origination does not rely upon any proprietary direct marketing channels. For now at least, it seems rarer for funds to have direct origination capabilities that mimics the borrower interface of the banking system.

Rather, fresh asset sourcing is typically via private equity firms, banks and other institutional advisors, with lending to existing borrowers also relatively significant. As mentioned above, the prevalence of sourcing new assets via sponsored deal flow more than any other non-brokered channel is widely in evidence, though data varies in terms of the extent of such dominance. This origination source is certainly more dominant in US than Europe, yet still some 75%-85% (according to Deloitte) of lending by funds in Europe comprise sponsored activity. (This range is corroborated noting info derived from selected direct lending fund pitch books). A few funds have lending JVs with banks, whereby the funds complement, or even fully assume, loans underwritten by banks to their own borrowers. Overall, we think the still-significant amount of dry-powder generally speaks to fund deployment bottlenecks given challenges in sourcing assets.

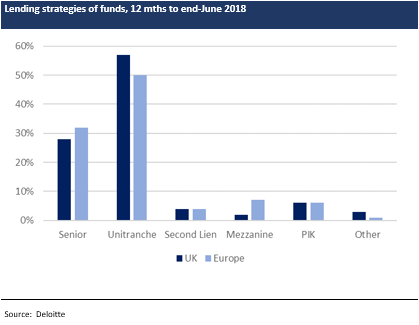

Loans originated by direct lenders in Europe hitherto tend to be dominated by unitranche formats by most accounts, with senior secured facilities most prevalent otherwise. Other loan formats such as senior unsecured, mezzanine or junior/ second lien facilities, convertibles, PIK loans and other hybrids (as well as derivatives such as TRS) make up around 15-20% of direct lending types according to Deloitte. Floaters are most common within the dominant senior secured and unitranche lending, with bullet maturities typically between 3 and 8 years. Loans are normally embedded with call and LIBOR floor protection features, as is common in the large cap leveraged loan market.

Direct lenders are also known to originate assets in the private placement markets in Europe, particularly in Germany and France via the established Schuldschein and EuroPP markets, respectively. (Involvement in the French market was catalysed by changes in insurance legislation in 2013 that allowed direct fund participation). However, the penetration of such alternative funds in these markets is not thought to be significant by any measure. Indeed there is a valid argument in our view that private placement markets are more competition rather than complementary for direct lending funds, being for the most part capital market alternatives to bank lending for mid-to-large cap borrowers and dominated on the buy-side by insurance and other institutional money. Certainly, in the case of the established and deep Schuldschein (ca. €90bn) market, standardised documentation, listing processes and legal governance better lends to mainstream institutional investor participation rather than to unlisted direct lending funds.

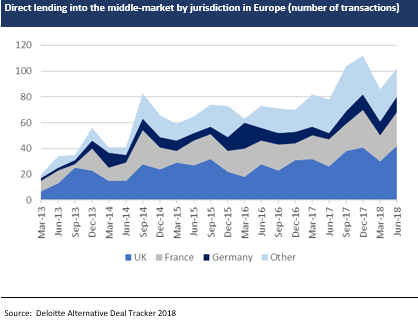

Geographically, most private credit mid-market activity centres on the UK, with France and Germany being the other two dominant jurisdictions. The UK’s historical dominance in such lending reflects the more liberal lending framework for non-banks and creditor-friendly recovery regimes. European direct lending opportunities were put in motion more recently, led by ELTIF (European Long-Term Investment Fund) regulations since end-2015 across the EU which kick-started alternative investment funds’ (AIFs) ability to originate loans, subject to certain criteria. Notably in this regard, German and – especially – French rules for non-bank lending were appreciably relaxed, though not fully liberalised noting that non-bank lending take-up thus far appears to be dominated by domestic funds. Many other European countries still explicitly require lenders to have banking licences in order to operate in domestic borrower markets.

Disclaimer

The information in this report is directed only at, and made available only to, persons who are deemed eligible counterparties, and/or professional or qualified institutional investors as defined by financial regulators including the Financial Conduct Authority. The material herein is not intended or suitable for retail clients.

The information and opinions contained in this report is to be used solely for informational purposes only, and should not be regarded as an offer, or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell a security, financial instrument or service discussed herein.

Integer Advisors LLP provides regulated investment advice and arranges or brings about deals in investments and makes arrangements with a view to transactions in investments and as such is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (the FCA) to carry out regulated activity under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA) as set out in in the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Regulated Activities Order) 2001 (RAO).

This report is not intended to be nor should the contents be construed as a financial promotion giving rise to an inducement to engage in investment activity. Integer Advisors are not acting as a fiduciary or an adviser and neither we nor any of our data providers or affiliates make any warranties, expressed or implied, as to the accuracy, adequacy, quality or fitness of the information or data for a particular purpose or use. Past performance is not a guide to future performance or returns and no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made regarding future performance or the value of any investments. All recipients of this report agree to never hold Integer Advisors responsible or liable for damages or otherwise arising from any decisions made whatsoever based on information or views available, inferred or expressed in this report.

Please see also our Legal Notice, Terms of Use and Privacy Policy on www.integer-advisors.com