Note: This publication is not intended or suitable for retail investors, please see Disclaimer below

22 May 2018

![]() P2P Marketplace opportunities (PDF version)

P2P Marketplace opportunities (PDF version)

In this commentary we highlight the growing footprint of marketplace loans in the capital markets in Europe, and discuss the key considerations in investing in these instruments. Our discussion of such opportunities precedes a review of growth trends and business fundamentals of this contemporary industry. We begin with a synopsis of our observations and views in the section below.

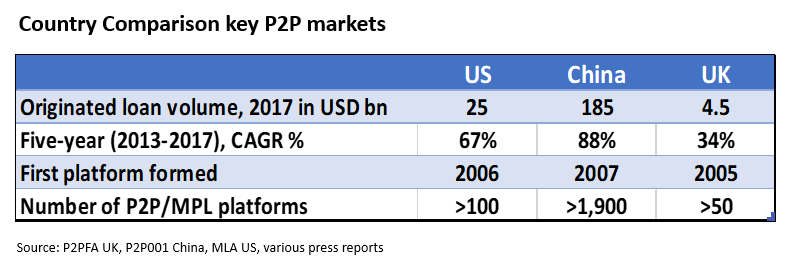

The UK can lay claim to the origins of the P2P/ marketplace (‘MPL’) industry as it’s generally known today, courtesy of Zopa which launched in 2005. This was followed by the likes of Prosper and Lending Club in the US over the next couple of years and Ppdai in China in 2007, in turn inaugurating three of the most established global jurisdictions for marketplace lending today.

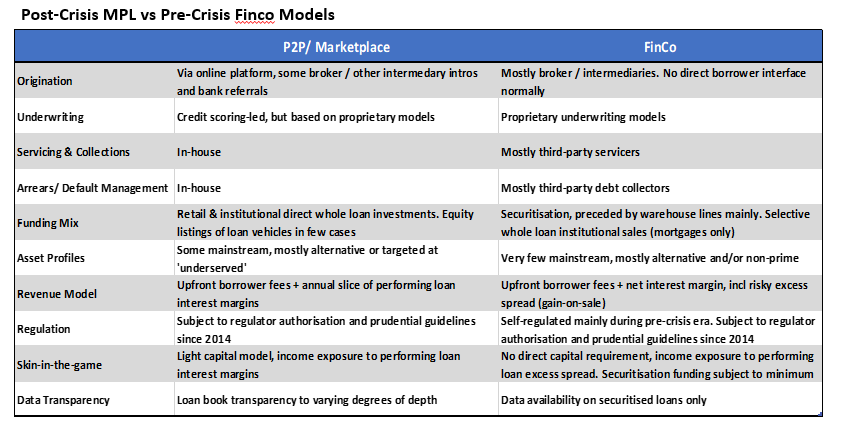

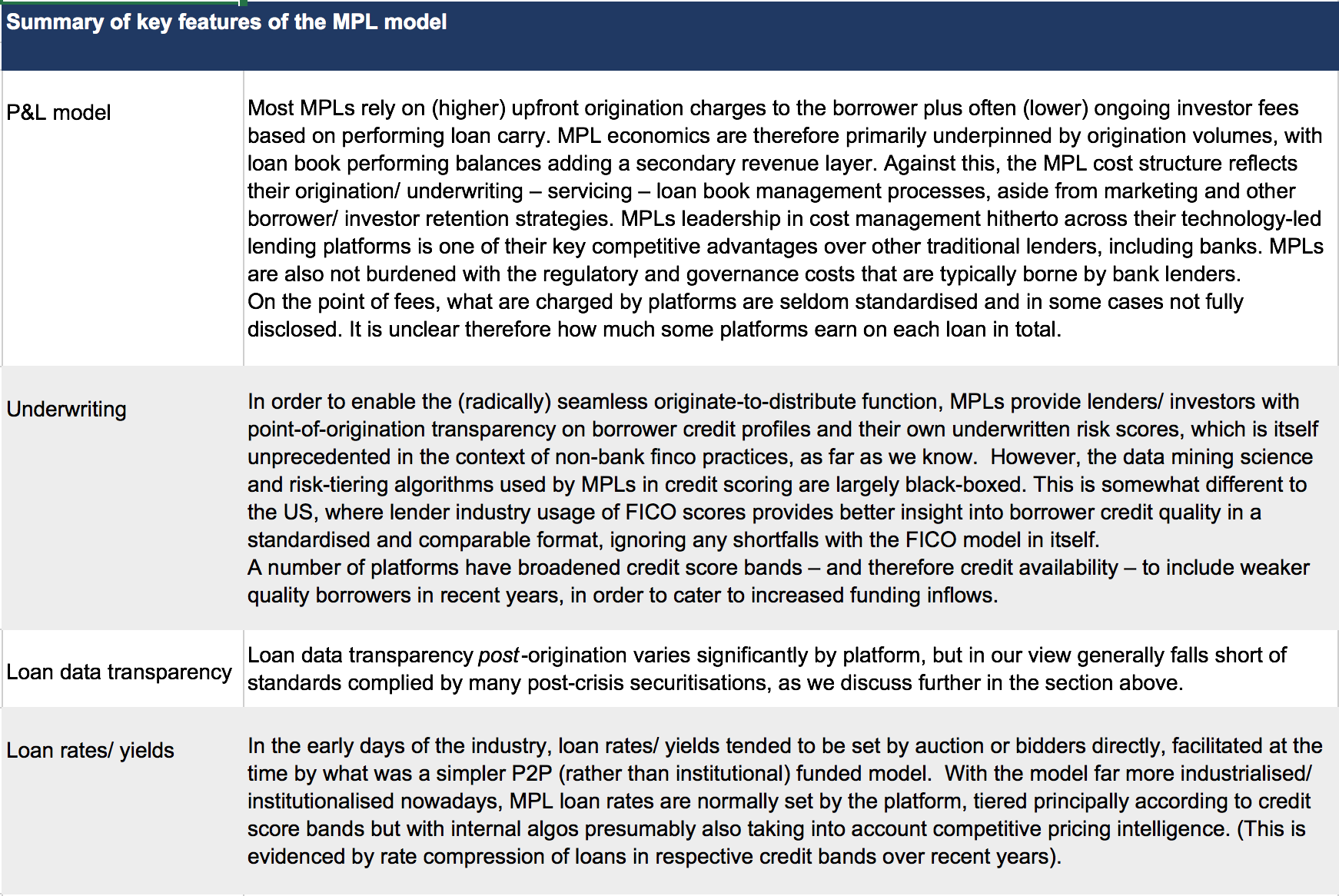

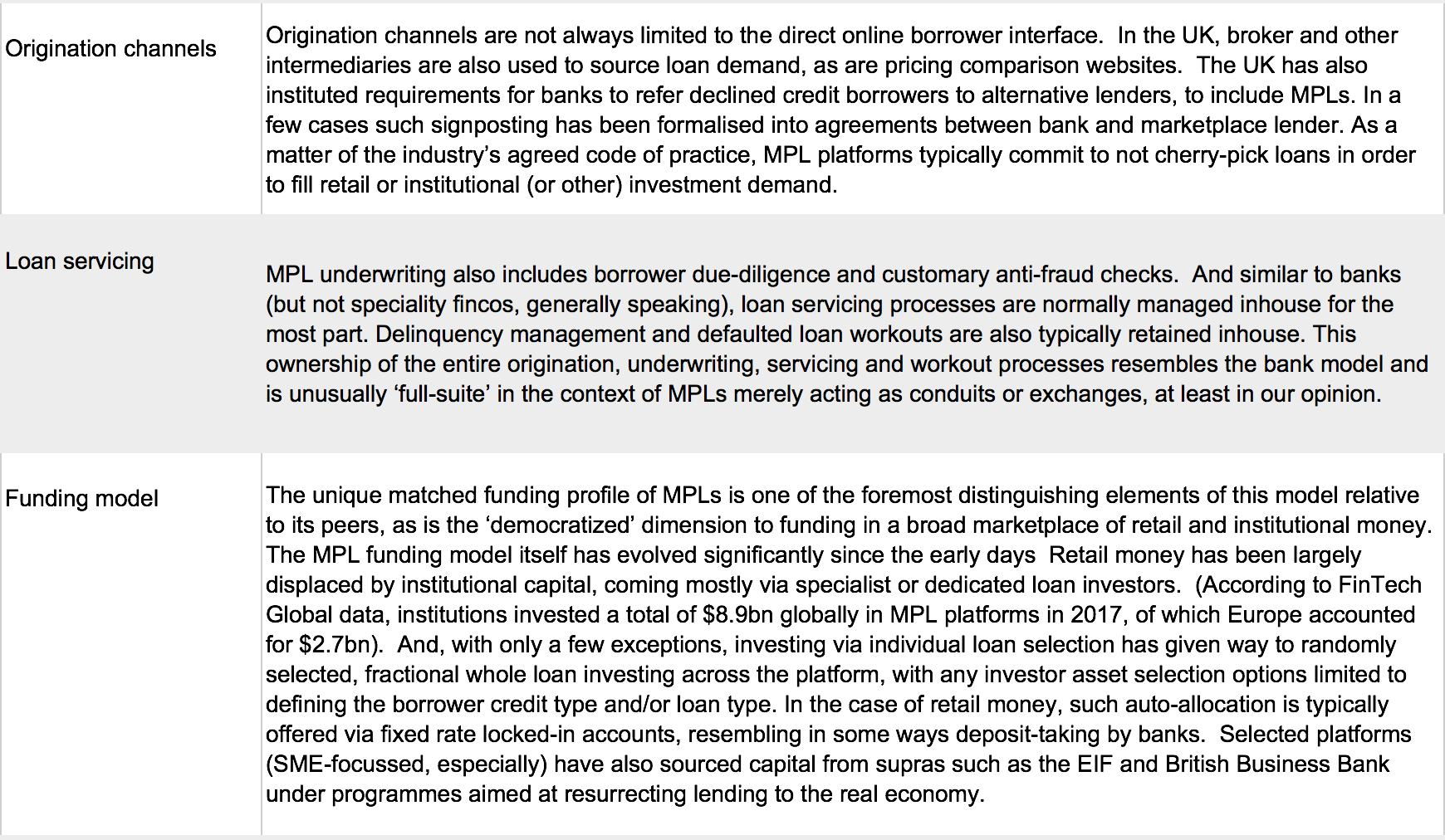

We see the contemporary P2P/MPL platforms as the most clinical manifestation of the originate-to-distribute non-bank model, which has of course existed in various guises over the past thirty years or so. MPLs are distinguishable for acting solely as conduits for borrowers to tap directly into non-bank lenders/ investors, without assuming any transitory asset or financing risks. (MPLs therefore do not employ maturity or risk transformation). The funding model has evolved significantly since the early days, with retail money being largely overtaken by institutional capital in recent years.

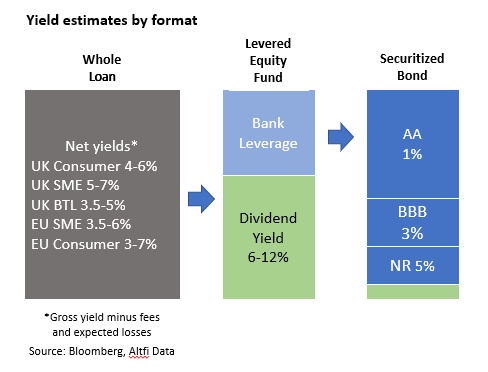

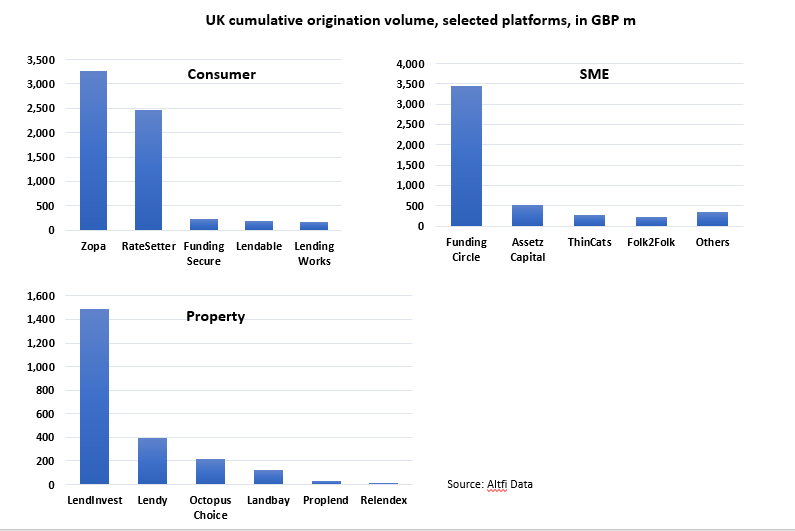

Looking through the headline trends, we find that much of the growth in lending volumes is driven by just a few platforms that have cemented their dominance in the market. Such platforms, and the more prominent institutional funds that buy their loans, make up the sponsors of MPL capital market instruments such as listed equities, securitised products and – more rarely – secured bonds. We find that yields across this equity – ABS – bond continuum seem to exhibit little absolute or directional correlation with underlying loan rates.

Going forward, we see the key considerations for capital market investors as centred on loan deterioration risks as well as operating/ funding vulnerabilities of the MPL model under any credit cycle downturn, with changes in regulatory regimes also important to watch:

-

- The susceptibility of MPL borrowers – across all credit bands – to a weakening in the credit cycle, whether economic or rates-led. We see this vulnerability as being greater in the case of MPLs (relative to mainstream lending by banks) given the targeted lending at underserved and/or alternative borrowers, aside from any inherent adverse selection risks. Yield sufficiency to cover losses is of course also a key related consideration

- Unusually for a non-bank credit intermediary, MPLs typically take ownership of the ‘full-suite’ of origination, underwriting, servicing and workout processes. We think platforms may face scalability challenges in managing this concentration of functions in a credit recession, potentially jeopardising the cost leadership enjoyed by the MPL model currently

- The question of origination/ underwriting discipline over a full cycle is also important noting that the MPL revenue model is heavily dependent on sustaining lending volumes, with platforms having seemingly little incentive to moderate origination growth for reasons of prudent credit management. Relatively thin skin-in-the-game may exaggerate these risks in more extreme cyclical conditions

- Vulnerability to institutional investment flows under any number of scenarios, to include rates/ yield curve normalisation

- Much is still yet to come by way of the regulatory regime for P2P/ marketplace lenders. Any regulatory ‘shock’ can bear significant effects on the very viability of the MPL industry, as the recent example of China shows.

Equally core to the investment thesis for P2P/ marketplace opportunities, in our opinion at least, is transparency, i.e., the quality of the lens into platform assets and their operating models, which based on our analysis does not seem generally sufficient in the case of most platforms to make a fully informed risk/return decision.

In terms of the outlook for the P2P/ MPL industry, we think it reasonable to assume that some well-managed platforms will navigate any headwinds to come and establish meaningful footprints in the credit system, likely at the expense of a number of competitor failures. But, by the same token, we see incumbent banks using their inherent dominance and balance sheet advantages to defend their lending territories, perhaps even re-intermediate some segments of the lending economy. Therefore, we believe that MPL models will establish themselves in alternative, niche pockets of the lending system, with banks remaining dominant in mainstream loan markets.

We expect established MPL platforms to better diversify their funding going forward, both in terms of broadening sources of current retail/ institutional capital while also tapping new channels of funding. To this end we see greater capital market opportunities to come in the MPL space.

Sizing the Capital Market Opportunities

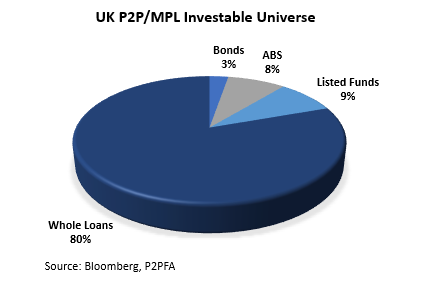

The unique aspect of the investable opportunities related to P2P/ marketplace loans is that the whole loans themselves are of course directly investable for the most part, in contrast to traditional lender intermediated loan markets. MPL platforms are designed specifically to appeal to direct whole loan investments, which make up the biggest share of this investable universe.

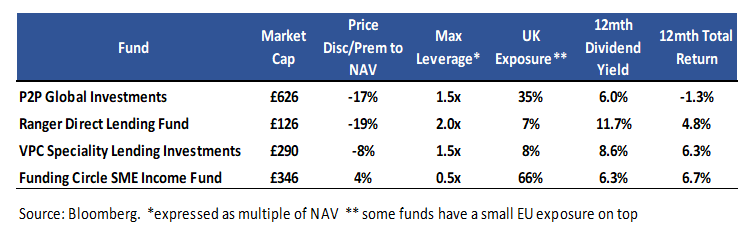

MPL loans are also represented in listed equity markets, namely via funds (and, more rarely, platforms themselves) that have invested in either multi- or single-platform loans. Such permanent capital vehicles are similar to loan REITs or BDCs, but without any investment perimeters or tax incentivised distribution requirements. MPL equity funds that invest in UK and/or European loans are mostly listed in London (and denominated in sterling) and structured as closed-end funds. Leverage is normally employed to enhance returns, with such gearing typically limited to 1.5-2x NAV, though such funds are often managed at a lower gearing level than the prescribed ceilings. Currently, investor-managed MPL funds listed in London are generally trading at discounts to NAV for various reasons, to include dividend disappointment and in a few cases high-profile platform failures among the underlying investments. (IFRS 9 adjustments have also shaved NAV in recent months). It should be noted that such funds may not limit asset allocation to MPL loans only – normally underlying investments can include platform equity, securitisation residuals, co-lending portions and other related asset financing exposures. Funding Circle’s SME Income Fund is the only listed UK fund that is sponsored by an MPL platform, with raised capital channelled into loans originated by the platform. There is a naturally greater universe of listed funds investing in MPL, or speciality finance asset more broadly, in the US.

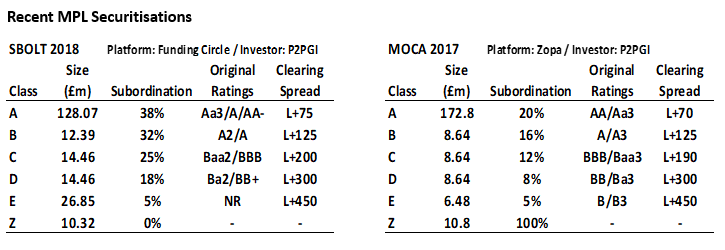

Securitisations of MPL loans are a growing asset class on both sides of the Atlantic. The very first MPL asset-backed transaction came to the US market in October 2013, with the first rated and broadly syndicated deal seen in January 2015. The UK’s MPL ABS debut came a year later. Since then, there have been four securitisations of MPL loans totalling just over £660mn, excluding the retention tranches. (By comparison, the US MPL asset-backed market has witnessed over $60bn of issuance volumes since its inception. $2.6bn of such bonds came to market in Q1 2018 alone). UK MPL ABS thus far has been issued under two programmes, each linked to established platforms in the consumer (Zopa) and SME loan markets (Funding Circle), respectively. Unlike the US where MPL platforms have been direct sponsors of securitisations, MPL ABS deal flow in the UK thus far has only seen investment fund sponsors, including managers with listed MPL funds. Such managers are normally motivated to tap the asset-backed market in order to term out leverage facilities in a cost effective manner.

Vanilla bonds secured on platform loan assets is another capital market format that has been seen within the MPL space, but such opportunities remain rare for now. In the UK, LendInvest and Wellesley are the only platforms – to our knowledge – to have issued such debt, with for instance the two Lendinvest issues totalling just £90mn targeted largely at retail investors.

Yields across the equity – ABS – bond MPL continuum seem to display little absolute or directional correlation with underlying loan rates, in our opinion. Starting with MPL loan yields, these range anywhere from 3% from the secured (often resi mortgage), prime borrower loan to over 20% for unsecured, essentially deep-in-alternative credit. We see the bulk of gross loan yields – excluding outliers – as ranging from 6% to 12% across the consumer (ex-mortgage) and small business borrower segments. Net yields adjust according to servicing fees charged of course. Servicing fees are typically in the 1% region where such charges are explicitly disclosed, though in some cases the servicing fee is neither clear nor transparent. In case of any defaults, recoveries flowing back to the investor will be netted of fees but, again, such fees are not made transparent in many cases. Funding Circle is a notable exception for being one of the rare few platforms to disclose recovery-related fees.

As against those asset yields, the liability side of MPL loan markets is relatively dispersed in terms of yields and returns. Listed equity and debt typically yield in the region of 6% (isolating dividend/ coupon returns only). Current yields on the former listed funds, which as mentioned normally use some degree of gearing to extract greater returns, can look inflated in cases where the equity trades at discounts to NAV without a commensurate compression in distributions. As a very cursory comparison, similar US funds as well as BDCs typically yield more generous dividends, reflecting a combination of greater gearing, higher asset yields and, in some cases, deeper discounts to reported NAVs.

Securitised MPL capital structures have rallied significantly since the debut MPL ABS. Senior (AA-rated) bonds have recently priced at L+75bps vs over L+200bp two years ago, while the most deeply subordinated tranches have recently cleared the market at ~5% floating-rate yields vs over 7% in early 2016. Current subordinated ABS yields are inside that of listed equity referencing largely the same assets, despite having greater structural leverage on account of being the second-loss, thinly sliced tranches of ABS capital structures. Such deeply subordinated ABS yields are also inside underlying loan yields, making MPL asset-backed liabilities look rich currently relative to the assets, yields in which have remained largely unchanged over the last couple of years. Given this tighter execution of ABS relative to MPL loan markets, it is of no surprise that term leverage provided securitisation capital markets have been attractive to asset owners and platforms alike on both sides of the Atlantic.

Exploring the Key Investment Considerations

We summarise below some of the key considerations in investing in MPL loans, whether directly or via capital market instruments such as equity and asset-backed securities. Our list is not meant to be exhaustive or substantive, rather a high-level assessment of pertinent investment consideration for this contemporary asset class.

Looking through the capital market instruments into the underlying MPL proposition, we think investment considerations should take into account two key inter-related factors – the first being asset quality and the second being vulnerabilities of the model itself. Assets originated by MPLs are for the most part established loan types, albeit largely alternative to mainstream bank product. But such alternative loan products typically have relatively demonstrable track records in the non-bank credit economy, at least in the UK. By contrast, the P2P/ marketplace business/ operating model in its current form is of course novel and substantially untested through different credit and economic cycles (only one platform, Zopa, experienced the 2008/9 crisis). Against the backdrop of the recent explosive growth of investment inflows and therefore lending capacity relative to their peers, we see merit in fully understanding the P2P/ marketplace platform model, not least given the apparent genesis parallels with the 2008 crisis.

Equally core to the investment thesis for P2P/ marketplace opportunities, in our opinion at least, is transparency, i.e., the quality of the lens into platform assets and their operating models, which we feel is crucial in being able to analyse outcomes that will influence returns.

Among what we see as the key investment considerations are:

1) Loan asset quality, loss predictability and the sufficiency of yields

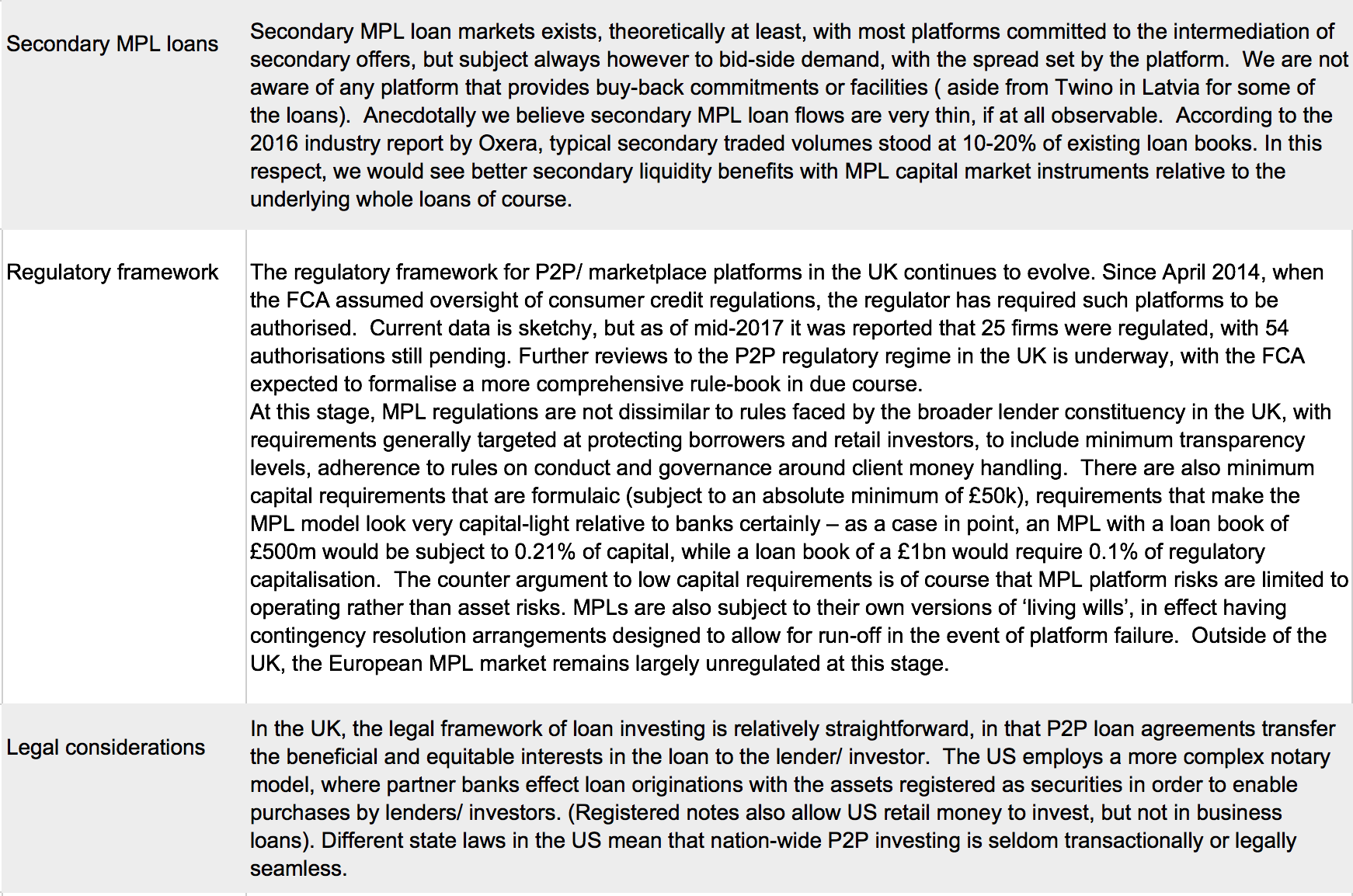

The default/ loss experience of most UK MPLs has been broadly consistent with expectations derived (and published) by the respective platforms, however such anticipated and actual credit outcomes have generally deteriorated moderately among the more recent vintages. As it stands, and as a very broad-brush observation, lifetime expected defaults for current loan production range between 4% and 6% generally among the lower-risk bands of consumer and SME loans. (We would caveat at this juncture that credit performance among MPL loans can vary significantly by loan and/or borrower type). Actual defaults among the 2015 cohort (i.e., loans aged roughly three years) have ranged around 3-4% for consumer assets and 2-3% for SMEs, with losses modestly lower given some recoveries, again ignoring the outlying weaker credit risk categories. For comparison, bank loan defaults are typically around 100bps lower than MPLs (unadjusted for duration or other loan variables), based on anecdotal evidence and selected bank reporting. But that one-dimensional view clearly does not take into account the perceptibly higher yields on MPL loans relative to bank loans, which hitherto has arguably generated better loss-adjusted returns relative to comparable bank loans. US MPL loan yields are typically higher than the UK, but largely justified by the higher default/ loss experience – for example, defaults among the weakest grade of small business loans can reach as high as 30% in the US.

Much of the overall higher default outcomes and expectations recently among established MPL platforms stems, we believe, from the inclusion of weaker credit bands/ borrowers in their lending remits over the past three years or so. Going forward, the key concern is the vulnerability of MPL borrowers – across all credit bands – to a weakening in the credit cycle, whether economic or rates-led. We see this vulnerability as being greater in the case of MPLs (relative to mainstream lending by banks) given the targeted lending at underserved and/or alternative borrowers, aside from any inherent adverse selection risks. That said, absent a credit or economic shock, we take some comfort in the fact that MPL internal risk models should benefit further as the market matures, with the greater depth of data allowing for better credit underwriting and default forecasting accuracy.

Should the current generally benign economic tailwinds reverse course and the MPL loan default drift worsens (this trend being visible already in unsecured consumer loan markets), loan yield sufficiency will be key in mitigating ultimate losses. With MPL internal risk-tiering models/ algos mostly undisclosed, it is unclear whether front book loan yields are adjusted as loss expectations or actual loss outcomes change, particularly if in an environment of lending competition and yield compression. (In other words, are MPLs price-makers or price-takers?) Investors in platforms with buffer funds should benefit from such yield management given the socialised first loss protection (i.e., the excess spread buffer funds are used on a first-come, first-served basis). We would note finally that static MPL portfolios – such as securitised pools – will not benefit from such loss-mitigating strategies.

2) Underwriting/ origination integrity in a volume-driven model

Adverse selection risks are valid considerations with MPL platforms given their competitive lending edge is primarily in alternative borrower markets not generally served by mainstream banks. MPL origination channels vary – aside from direct online applications, loans are also known to be sourced via broker intermediaries, pricing comparison websites as well as bank referrals of declined credit. There is generally very limited data available on the breakdown of different loan origination sources, nor indeed on the credit performance disparities (if any) between loans originated via the different sources. (We note however a recent press report stating that only a very small fraction of declined credit referred from banks are accepted for MPL loans).

The question of origination/ underwriting discipline over a full cycle is particularly important with MPLs given there is seemingly little incentive to moderate lending volume growth for credit management reasons, on account of the model’s revenue-dependency on originations given borrower upfront fees, which range from 1.5% to 6% depending on loan type and tenor. Regulated banks are subject to counter-cyclical measures where lending volumes become outsized relative to norms (as was the case with UK bank consumer lending late last year), whereas MPLs face no such prudency brakes. As far as we can see, the only counter-cyclical control on MPL lending volumes is through (potentially) reduced investment inflows as investor appetite becomes more credit and/or rates-sensitive over the cycle.

Lapses in underwriting/ origination discipline in the case of ‘new’ online lending models have plenty of precedence going back to the early 2000s (Belgium mortgage lender EuropeLoan and US credit card firm NextCard, to name but a few). Notwithstanding how the digital lending model has matured since then, there have been a number of P2P/ marketplace platform failures much more recently in the UK and Europe, the highest profile case being Sweden’s TrustBuddy. In the US, LendingClub – one of the largest MPL players – has faced significant issues related to origination misconduct in recent years.

3) Skin-in-the-game, or lack thereof

MPL lenders have far less skin-in-the-game compared to traditional asset risk takers, which we see as a very relevant consideration following on from the underwriting slippage risks described above. The counter-argument here is that MPLs can afford to be thinly capitalised as they do not warehouse asset risks in their role as conduits between loan investors and borrowers. To be sure, other intermediation-only platforms such as brokers and exchanges do not have to provide skin-in-the-game either. But we think the key difference in the case of MPLs is their sole ownership of the entire origination, underwriting, servicing and workout management of credit as part of the lender/ investment proposition, which arguably demands some alignment of interest. Realistically, of course, skin-in-the-game is no replacement for prudent management aimed at long-term business viability, which would only be demonstrable in a credit recession. It remains to be seen which platforms will successfully manage the challenge between volume growth (which drives revenue) and credit discipline needed in the long run.

As it stands, MPLs benefit from a capital-light regulatory model, with for instance a £1bn MPL loan book requiring just 0.1% capitalisation. (Presumably such regulatory capital requirements have been sized to reflect operating risks only, given no asset risks). Precedence in the non-bank credit economy suggests that trailing loan book income and reputational risk concerns are insufficient in themselves as skin-in-the-game surrogates in any credit cycle fallout. It should be noted that ‘buffer’ or first loss funds provided by some platforms are funded normally out of loan excess spread rather than own capital.

Were an MPL platform to issue ABS in order to fund loan investments, the platform would require to hold a minimum 5% of the capital structure under securitisation regulations. (This is the case for platform-sponsored ABS in the US). MPL loan owners such as funds who securitise are subject to this retention rule of course.

4) Scalability challenges over the cycle

Most MPL platforms are young and still generally thinly resourced, yet (unusually for a non-bank model) tend to retain all loan origination, servicing and arrears management inhouse. A key investment consideration in our view would be the ability of platforms to manage this concentration of functions and deliver incremental resources in order to cope with a credit cycle downturn, particularly if loan performance stress coincides with reduced funding/ origination volumes. (Revenues are squeezed by both lower servicing and origination fees in this scenario)

In short, we see scalability challenges to deal with any credit recession without impacting the cost leadership currently enjoyed by MPL platforms. And not being able to fully invest in loan recovery processes when needed most may exaggerate loss outcomes ultimately.

5) Vulnerability to institutional investment demand

MPL funding has seen a noticeable rotation to institutional money over recent years, mirroring the generally reduced reliance on retail funding. This shift has undoubtedly had a powerful impact in cementing the lending footprint of a few MPLs. Investment rationales for institutional investors include the generous yields, low correlation to listed assets and the diversification benefits of otherwise inaccessible credit sectors such as consumer or SME loans.

But the shift to institutional money arguably means that funding is less ‘sticky’ that would have been with retail money. Such money is susceptible to flight under any number of scenarios, to include (potentially) rate normalisation, other macro or credit events and indeed any negative headlines in the MPL space.

By contrast, retail money is likely to be stickier, particularly if invested under ISA allowances in the case of the UK. In the US, a number of the larger and more established platforms have developed hybrid funding strategies that span retail, institutional as well as own balance sheet funding, the latter mostly via asset-backed debt programmes.

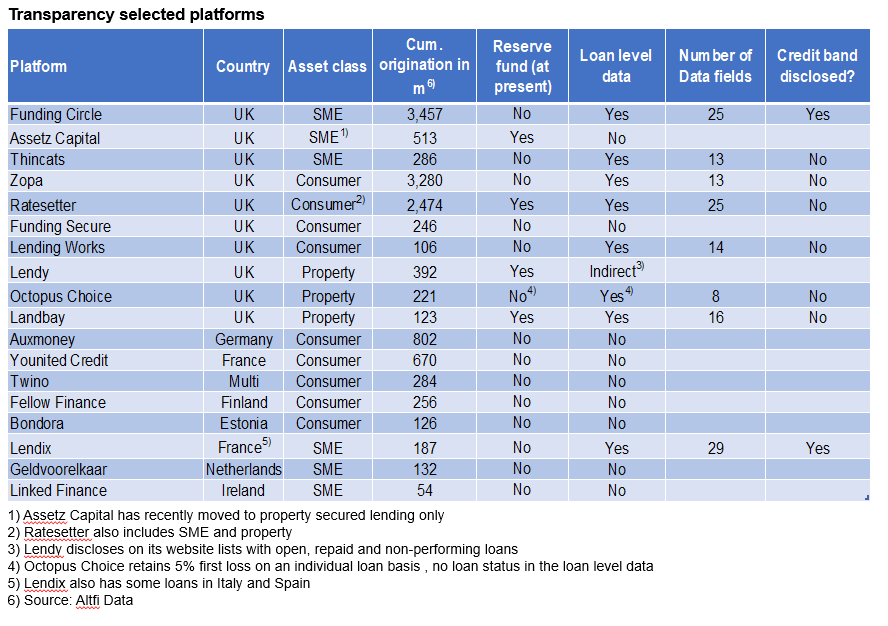

6) Transparency considerations in the context of visualising risks over the horizon

MPL platforms are certainly more transparent than any other non-bank finco model, in that credit underwriting outputs and loan terms/ features are made readily available at the point of origination. That aside, platforms also provide historical data on credit performance of their originated loan stock, to varying degrees of depth.

But given the non-recourse nature of P2P/ marketplace lending and taking into account some of the other risk factors outlined above (potential drifts in underwriting discipline, lack of skin-in-the-game, other operating challenges and credit vulnerabilities as cycles turn), the issue of sufficient data transparency in order to clearly identify current credit trends as well as visualise borrower payment behaviour patterns is a key investor consideration, in our opinion. By ‘sufficient’ we mean the depth of loan book information such as borrower and loan profiles, default and loss statistics, etc, produced in a line-by-line format.

Our high-level review of selected MPL platforms, as summarised in the table below, highlights disparities in the quality of loan book data transparency. (We looked at the more established platforms that draw funding from both institutional and retail money, thus excluding the likes of Market Invoice, Lendable, Lendinvest Creditshelf, etc. given their non-retail focus. We also excluded aggregator platforms).

Foremost, we have observed a noticeable difference in disclosure standards between UK and European platforms, with transparency provisions among the latter platforms remaining relatively basic, if not minimal. The one notable exception is Lendix in France. And even within the UK, where most (but not all) platforms provide good aggregated data on yields and defaults/l losses by cohorts as well as fee structures, there appears to be noticeable differences in the depth of this information provided between different platforms, with MPLs adhering to the P2PFA standards generally providing better transparency as well as data standardisation. There is, however, typically very limited information provided on other important trends such as origination channels, loan rejection rates, underwriting scoring models, collection and workout resources, etc.. It is also unclear if and how ratings are updated, hence rating migration tables are not available. Moreover, internal rating methodologies are updated taking into account new data which makes comparisons with historical rating performance potentially difficult.

Mandatory data requirements for securitisations, in the context of complying with central bank (BoE/ ECB) criteria, provides a useful yardstick to measure the depth of loan-level data provided by MPL platforms. For the most part, we note that platforms publishing loan books provide fewer loan-level data fields than that required of central bank-eligible securitised products. To make our case, we would note that the ECB consumer, SME and residential mortgage data templates have 46, 48 and 55 (mandatory) data fields, respectively, that needs to be filled. (See table below for MPL comparisons

7) Regulatory outcomes

Regulatory changes to come also poses risks to the MPL model, but perhaps also competitive benefits to platforms that are able to adopt to such demands and build businesses around any new regulatory regimes. Thus far, the UK has implemented a broad-based rule book for MPLs, following on from the requirement for such platforms to be authorised by the FCA. European platforms remain largely unregulated for now.

In the UK, the FCA’s full review of the industry and further regulatory initiatives are still pending. Both the UK and the EU launched regulatory action plans in Q1 this year, namely the EU Fintech Action Plan and UK Fintech Strategy, respectively, intended to cover the full gamut of technology-based industries – including marketplace platforms – within financial services. What comes out of these initiatives is of course still unclear, but we sense from the tone of these plans that the intent is to design regulatory frameworks without diminishing the growth and/or innovative capacity of this sector.

Much is still yet to come by way of regulating P2P/ marketplace lenders. In the case of MPL platforms, we see the direction of regulation being guided by the fundamental perspective regulators will ultimately have of MPL models – that is, are these platforms ‘shadow banks’ or ‘shadow asset managers’? Lending directly into the real economy and borrowing using a combination of institutional money and deposit-like retail facilities gives some credence to the view that MPLs resemble banks. Or conversely, MPLs can be seen simply as asset allocators of institutional and retail capital that have specific appetite for exposure to the assets in question, without employing any maturity or risk transformation. Our overall view is that any treatment of MPLs as shadow banks will ultimately mean a more comprehensive and stringent regulatory regime versus thinking about these platforms as anything else. We are also of the opinion that some further regulatory oversight – in terms of borrower/ investor protection, lending conduct and overall operating governance – is likely inevitable any which way, to potentially include greater capital requirements.

Any regulatory, or indeed legal-related, ‘shock’ can bear significant effects on the very viability of the MPL industry. In the UK, a number of platforms are known to have shut down rather than embrace the FCA’s (relatively light, for now) requirements. The US has also witnessed certain regulatory and legal disruptions, notably including the Madden vs Midland case which threatened the fundamental viability of nation-wide MPL models. But for the most instructive example to understanding the potential impact of unfriendly regulations, one only has to look to China. Over the course of 2017 and into this year, there has been a significant tightening in the regulatory framework for P2P lenders in response to both misconduct cases and, more generally, demands to rein in the shadow financial system. The new regime includes usury rate ceilings, borrowing caps and other restrictions in lending practices, limits on asset-backed bond issuance and funding from financial institutions, aside from requiring all lenders to file for authorisation. Most commentators have argued that the scale of the regulatory clampdown will trigger a material shrinkage in the P2P industry, with only a few platforms being able to survive going forward.

There is one, investor-friendly aspect of the regulatory regime in the UK that we think is deserves mention, that is, the requirement for platforms to have “living wills” in place. Similar in some sense to how securitisations work, the rules are designed to allow for an asset run-off in cases where a platform fails. This is untested of course, but we still like wind-down frameworks over any unorderly outcome in the event of MPL dissolutions.

Brief Thoughts on the Outlook for the P2P/MPL Model

There has been no shortage of commentary talking to the outlook for the P2P/ marketplace industry since this model became better entrenched in different lending economies. Opinions are generally bifurcated into the “bubble and unsurvivable” or the “revolutionary, here to stay” camps.

In this commentary we do not profess to have undertaken any substantive analysis to be able to fully discuss the long-term outcomes for the MPL industry. That said however, in the section below we articulate our thinking in this respect.

Our simplified view is that there are two key outcomes to consider:

- Taken in isolation, can the contemporary marketplace operating and funding model survive any ‘shocks’ to come, whether via credit recessions, investment outflows or regulatory tightening, to name but a few? Even in the absence of any such shocks, it would be reasonable to assume that the current explosive growth trend will be exhausted before long, putting pressure on the weaker platforms. In the US, MPL lending actually peaked in 2015, with growth rates gradually moderating since then.

- Will incumbent banks re-intermediate lending markets currently occupied by MPLs, namely by cloning the technology-led infrastructure or, indeed, by acquiring established players? Most commentators agree that the MPL model will not have an enduring advantage over the bank model, simply given the ease of replication of any innovation, whether in terms of borrower origination interface or underwriting risk models or otherwise. But equally, we see the banks’ current competitive advantage from asymmetric information being eroded with PSD2 and the UK Open Banking Standard forcing greater sharing of such data.

Reflecting on the points above, our sense is that – like any young, fast-growing industry – there will be well-managed platforms that navigate any headwinds to come and establish meaningful footprints in the lending economy. Such survival could well be underpinned by sector consolidation, and potentially also at the expense of some competitor failures. But, by the same token, incumbent banks are likely to use their inherent dominance and balance sheet advantages to defend their lending territories. Therefore, we think that MPL models that outlive the ‘bubble’ will establish themselves in alternative, niche pockets of the lending system, with banks remaining dominant in mainstream loan markets. Where there is overlap in targeted lending segments, we see bank-MPL lending JVs becoming more prominent, a trend that is already visible in the US.

There certainly is precedence for such complementary lending ecosystems, not least in the US where the non-bank credit economy has proven resilient time and again to cyclical fortunes. On this side of the Atlantic, we see the UK as more naturally suited to this parallel bank/ non-bank credit system, given both the regimented nature of bank lending on the one hand and the deeper institutional (and capital market) appetite for loan credit assets on the other. And the fact that certain MPL investments can now count towards household ISA allowances is a powerful de facto endorsement of the model by policy-makers, in our view. Still, we do not see such ISA inflows cannibalising deposit-taking by the incumbent UK banks.

By contrast we see the MPL model facing greater challenges in core Europe over the foreseeable future. Not only are there generally wider boundaries to bank lending appetite, but there is also (concurrently) more limited ‘alternative’ lending opportunities. Or put differently, any alternative borrower segments tend to be further out the non-conforming spectrum, whether measured by credit quality or otherwise. (We note, for example, that there is little precedence for alternative non-bank credit models successfully surviving in a highly-banked economy like Germany). There will likely be exceptions of course in terms of countries and/or lending pockets for MPLs to operate viably. In this regard we see it as encouraging that European policy makers have explicitly recognised the role non-bank lenders can play as alternative sources of financing (subject to oversight, however), as spelt out for instance in the EU’s Capital Markets Union blueprint.

There can be no certainty as to how MPL models will ultimately look like as the sector matures. But we see two key potential developments to come, aside from the focus on alternative loan markets as outlined above. The first is based on our earlier articulated view that the concentration of underwriting, origination, servicing and credit management of loans is likely to be tested in any downturn, leading potentially to more autonomised functions provided by third-parties, perhaps leaving MPL platforms as origination conduits only. (This will resemble more traditional finco models in some respects). The second is that the more established MPL platforms will likely seek to fully diversify their funding sources. We see this featuring both in terms of broadening sources of current capital (that is, tapping institutional and retail money through more diversified formats) as well as funding strategies that reach into new channels of funding.

Capital market MPL opportunities to expand further

Following on from our point made immediately above, we see greater capital market opportunities related to MPL assets going forward in Europe.

Such opportunities should manifest via listed equity, securitised debt and potentially other bond formats. Asset-backed bonds, in particular, are likely to be more fully embraced given the compelling financing costs for what are normally highly ‘securitisable’ assets. We also see a shift to platform-sponsored opportunities, potentially at the expense of the current model of investment fund-sponsored capital market instruments. Listed equity markets, for instance, remain largely untapped by the established MPL platforms – by contrast, investor-managed multi-platform equity funds have faced challenges recently, as reflected in typical NAV discounts. (In one high profile case currently, the deep NAV discount has attracted an activist investor who is using their stake to attempt forcing for a wind-down of the MPL fund).

P2P/Marketplace Explained

Genesis of the Industry

The UK can lay claim to the origins of the P2P/ marketplace (‘MPL’) industry as it’s generally known today, courtesy of Zopa which launched in 2005. This was followed by the likes of Prosper and Lending Club in the US over the next couple of years and Ppdai in China in 2007, in turn inaugurating three of the most established global jurisdictions for marketplace lending today.

We think it’s worth defining this “P2P/ marketplace” industry in the first instance, in particular distinguishing this model from the broader online or digital lending universe, which in itself has also grown rapidly in recent years. Such online lending platforms share similar ‘front-end’ (i.e., borrower-facing) lending infrastructure with marketplace platforms, but with the key difference that the latter’s funding or liability side is sourced from a broad marketplace of retail and institutional investors. It is this democratized funding profile that we use to define MPL platforms.

Notwithstanding the platform debuts in the mid-2000s, it was not really until the post-crisis era when the P2P/marketplace phenomena took hold, led by breakneck expansion in the US and Chinese markets, followed soon after by the UK and, most recently, Europe. Factors underpinning the success of the P2P/ marketplace model are now well-documented, to include the digitally-enabled, streamlined and cost-effective underwriting and origination process which affords quick lending decisions, bringing a radical change to the typical customer journey relative to practices of the incumbent bank lenders. Funding appetite from yield-starved retail and institutional investors, along with seeding by supras aiming at fostering the alternative lender industry, also helped to propel the model in the post-crisis era.

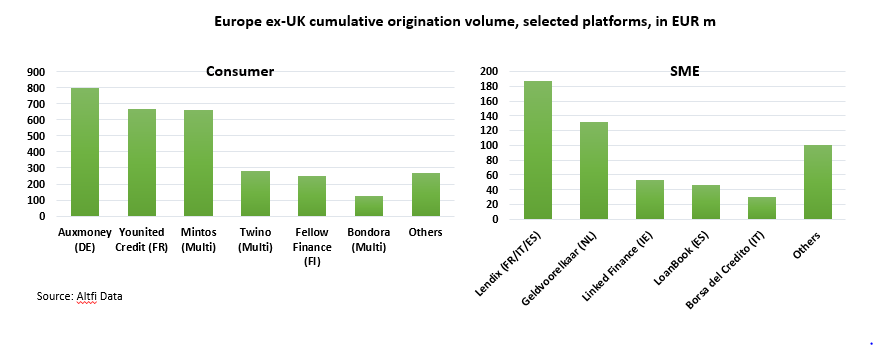

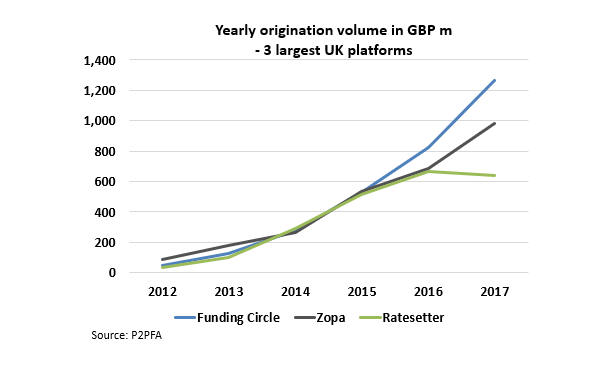

Growth of the UK MPL market accelerated noticeably from 2014. Despite the proliferation of the number of marketplace platforms, much of the growth in lending volumes was driven by just a few platforms that cemented their dominance in the market. The industry in Europe still remains at an early stage, and – like the UK – concentrated among a select few platforms and lending aggregators. What’s notable about the European MPL market is the preponderance of bank and/or insurance JVs with MPL platforms (compared to the UK, at least), though we would note that some such platforms are more online lenders than MPLs, strictly speaking. At this time Germany and France remain the largest MPL markets in Europe.

There are around 50 MPL platforms in operation in the UK today, following compound growth of some 30%+over the post-crisis period, with business lending (SME loans and invoice financing mainly) growing the most sharply. On any measure, the growth of the P2P/MPL market in the UK has significantly eclipsed the growth of any other lender type, to include the loan books of challenger banks that came into being at roughly the same time as marketplace lenders.

Yet total cumulative MPL lending in the UK stands at almost £9bn, according to the P2PFA, representing (approximately) just 2-3% of total gross lending, isolating the consumer (non-mortgage) and SME loan markets. The stock of MPL loans outstanding stands at around £4.5bn, which is less than 1% versus loans outstanding in the broader credit system. In Europe, the MPL footprint in loan markets is at a fraction, still a rounding error as it were. So while the growth of this contemporary lending model has been nothing short of staggering, its penetration into the broader (bank-dominated) credit economy remains minimal thus far. For this and other reasons, we are cautious in talking up the “disintermediation” accomplishments of such lenders – rather, we see MPLs as arguably more complementary to incumbent bank lending, as we outline further below.

For now, there seems to be no let-up in MPL lending growth in the UK and Europe, with 2017 breaking new records again with the UK seeing total originations of just over £5bn and Europe just over €1.5bn, according to AltFi. On the funding side, most of such platforms have long since evolved from retail or “P2P” models, with institutional money largely fuelling growth in recent years. A few of such institutional managers have tapped the capital markets for leverage or capital, as have selected MPL platforms directly. (See discussion above)

By contrast, the US MPL market witnessed around $25bn of originations in 2017, but notably lending volumes have gradually declined from the peaks reached in 2015. Yet, despite not having any head start on the UK, the P2P/MPL industry in the US (and China, for that matter) is noticeably larger at this stage, measured both in absolute terms of course (given the sheer size of the credit economy) and also in proportion to the overall lending markets. The US, which is of course the closest comparable to the UK in terms of the credit industry backdrop and lending (or disintermediation) opportunities, is also more matured in terms of MPL model visibility, funding reach as well as the depth of the overall MPL/ online lending ecosystem, aside from lending penetration. Bank – MPL JVs are becoming increasingly common in the US loan market

Profiling the P2P/ Marketplace Model

We see the contemporary P2P/MPL platforms as the most clinical manifestation of the originate-to-distribute non-bank model, which has of course existed in various guises over the past thirty years or so. But unlike non-bank (often securitisation-based) lenders of the recent past, MPLs stand apart for acting solely as conduits for borrowers to tap directly into non-bank lenders/ investors, in effect playing a similar intermediation role as exchanges rather than that of outright lender. MPLs do not generally assume transitory asset or financing risks, and do not therefore employ maturity or risk transformation.

Disclaimer:

The information in this report is directed only at, and made available only to, persons who are deemed eligible counterparties, and/or professional or qualified institutional investors as defined by financial regulators including the Financial Conduct Authority. The material herein is not intended or suitable for retail clients. The information and opinions contained in this report is to be used solely for informational purposes only, and should not be regarded as an offer, or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell a security, financial instrument or service discussed herein. Integer Advisors LLP provides regulated investment advice and arranges or brings about deals in investments and makes arrangements with a view to transactions in investments and as such is authorised by the Financial Conduct Authority (the FCA) to carry out regulated activity under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA) as set out in in the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Regulated Activities Order) 2001 (RAO). This report is not intended to be nor should the contents be construed as a financial promotion giving rise to an inducement to engage in investment activity.Integer Advisors are not acting as a fiduciary or an adviser and neither we nor any of our data providers or affiliates make any warranties, expressed or implied, as to the accuracy, adequacy, quality or fitness of the information or data for a particular purpose or use. Past performance is not a guide to future performance or returns and no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made regarding future performance or the value of any investments. All recipients of this report agree to never hold Integer Advisors responsible or liable for damages or otherwise arising from any decisions made whatsoever based on information or views available, inferred or expressed in this report. Please see also our Legal Notice, Terms of Use and Privacy Policy on www.integer-advisors.com