27 April 2018

In this the second part of our series on investable loan markets in Europe, we look at corporate-related opportunities. Unlike mortgage or other inherently illiquid asset finance markets, corporate loan credit-related opportunities manifest directly to a large extent in the capital markets via tradable loan markets, whether in syndicated investment grade or high yield/ leverage loan sectors. Our proceeding discussion focusses more on the scope of indirect investment opportunities, that is, investing in isolated portfolios (whether managed or static) of corporate loans via debt, equity or fund instruments, as opposed to directly buying singe-name corporate loan credit.

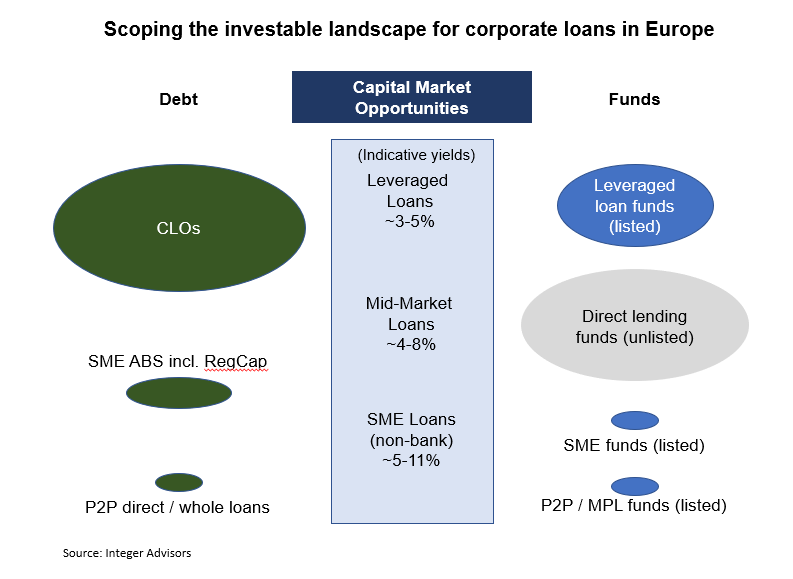

The opportunity suite is certainly broad when it comes to corporate loans, not to mention diverse from an asset/ credit perspective. Investable instruments that reference corporate loans range from securitised products (CLOs, mostly) to listed equity and unlisted direct lending funds to the more contemporary whole loan opportunities presented by marketplace platforms. To better conceptualise this product suite, we will need to distinguish the European corporate loan market by borrower type.

Taken in its entirely, corporate loans in Europe continue to be dominated by banks, to a much greater degree than say in the US. Bank loans outstanding as at end 2017 stood at €5.2trn (source: ECB/EBF). Non-bank ownership of corporate loans – from which of course most investable opportunities stem – has certainly increased with post-crisis bank disintermediation, but remains comparatively low, estimated at less than 10% of the stock of loans outstanding. (By contrast, such institutional lending accounts for 70-80% of the US loan market). Non-banks in the corporate loan markets comprise CLOs and direct lending/ marketplace funds for the most part. Other speciality finance lender models substantially did not survive the 2008/9 crisis.

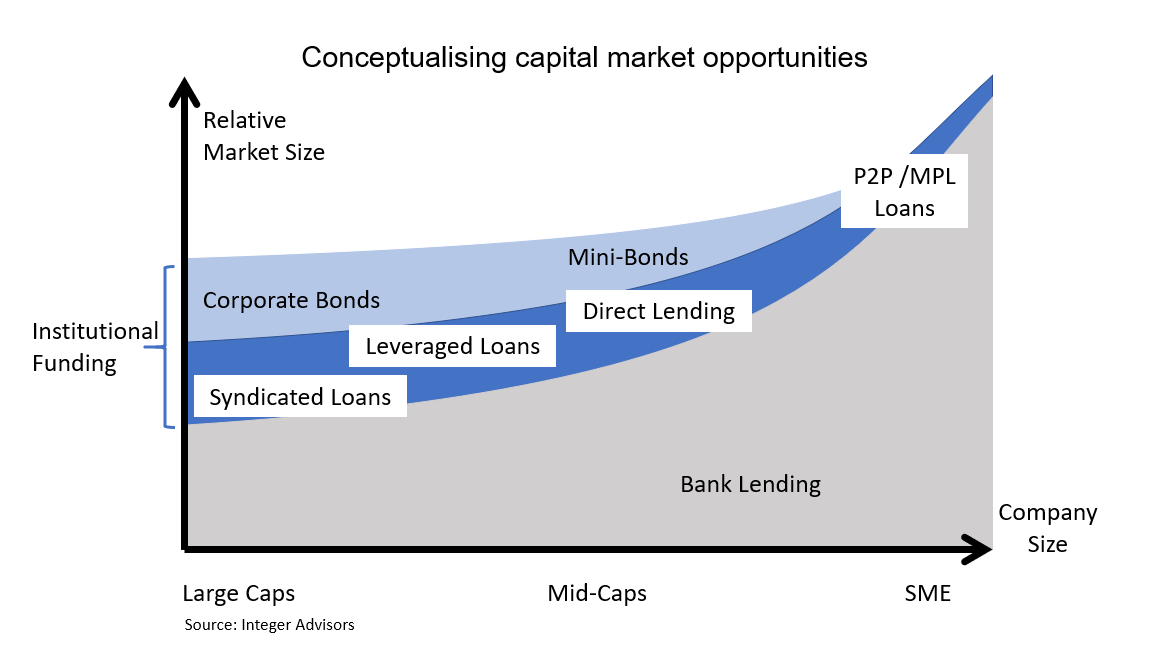

The large-cap segment of the corporate loan markets – namely syndicated high grade and leveraged loan markets – is by far the most institutionalised, certainly in the case of the high yield leveraged loan market where the extent of bank participation in new deal flow is typically no more than 25% currently. At the other end of the continuum, SME loans continue to be owned overwhelmingly by the banking system despite disintermediation efforts in the post-crisis era, with a fraction (albeit growing) of such borrowers currently sourcing credit from non-bank entities such as direct or marketplace lenders. The corporate economy that falls in between – loosely defined as the mid-market loan space – is also largely bank-dependent for borrowing, however there is a deeper footprint of non-bank lenders. But as we discuss further below, little of this institutional activity in the mid-cap market translates into capital market investable opportunities.

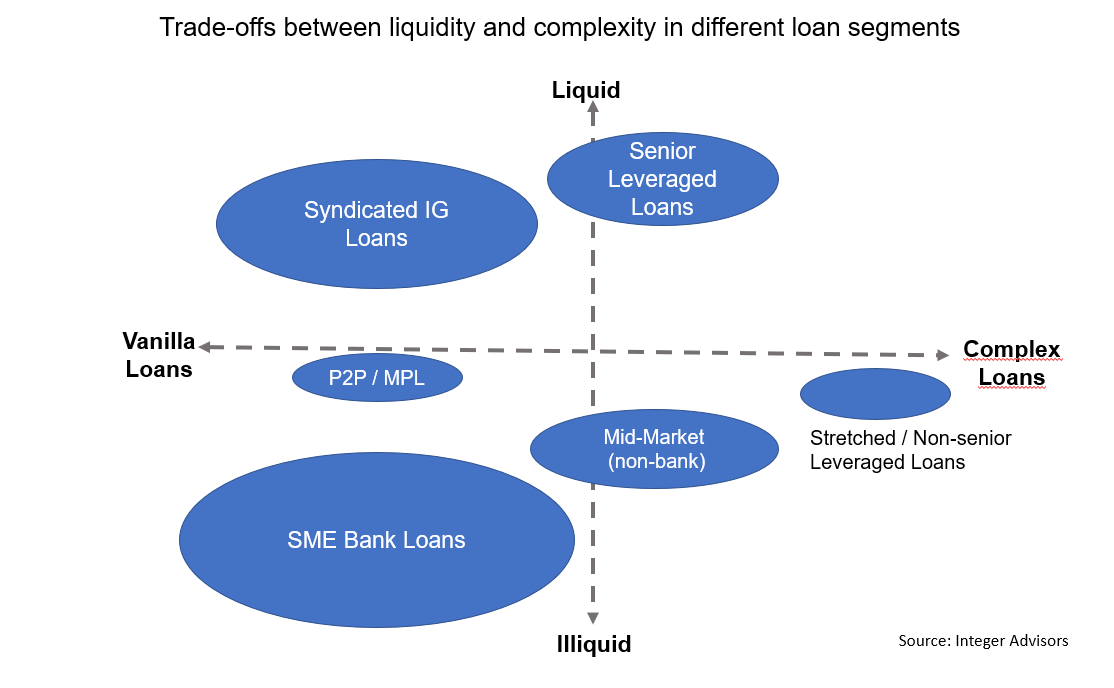

Mirroring both loans sizes and the degree of non-bank institutionalisation, large loan and highly institutionalised markets such as leveraged loans are of course the most liquid (by tradable depth), while – at the other extreme – SME loans are entirely illiquid for the most part. What we see is that the yield continuum from large to small corporate borrower loan markets looks linearly correlated to liquidity, with loan yields the richest in the larger loan / more liquid segments and cheapest in illiquid small balance markets otherwise dominated by banks. The same generally extends to the capital market instruments referencing the different loan types, save for when returns are enriched by instrument gearing. We caveat of course that these simplistic observations provide just one half of the risk/ return picture, with no account taken of the risks, which can vary materially by loan/ borrower types.

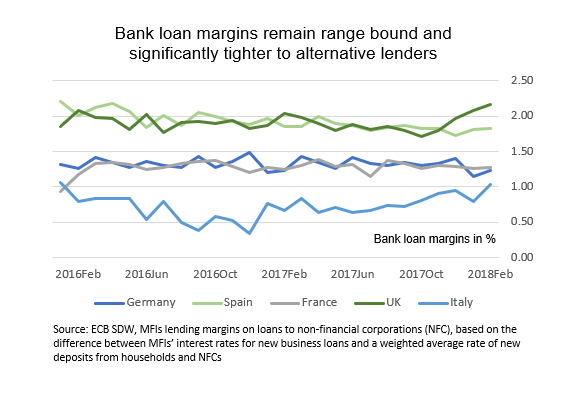

Across all sectors without much exception, bank loan margins are tighter (often noticeably) than non-bank lending margins. This disparity is explained by a number of historical as well as more topical factors, in our view. Banks have been direct beneficiaries of generous central bank funding accommodation and specific programmes designed to incentivise corporate lending (to SMEs particularly), while enjoying a powerful head start over the newer generation of non-bank lenders in terms of borrower relationships and credit intelligence. Similar to other asset finance markets therefore, non-banks have been squeezed mainly into ‘alternative’ sectors, which in the case of corporate lending is mostly special situation lending like leveraged loans as well as other pockets of the loan markets that are underserved by banks, whether for reasons of capital-intensity, complexity or other risk-related factors.

Large cap markets: The greatest degree of institutionalisation, the biggest investable footprint

Large loan markets stretch from syndicated investment-grade loan markets to high yield, leveraged loan sectors. There is a greater balance of lending volumes in the IG market of course. The outstanding leveraged loan market stands at ca. €280bn (including bank lines), of which more than half are institutional facilities.

Syndicated high grade loan markets have faced relatively little lender/ investor disruption over the last (post-crisis) cycle. Certain countries have developed their own unique loan capital markets with direct investment incentives, the Schuldscheine in (mostly) Germany (€27bn issued globally in 2017) being an example. The capital market footprint away from direct investing is limited from what we understand, for this reason we do not focus on this particular segment in this commentary.

Leveraged loans, CLOs and loan funds

By some contrast the leveraged loan market has evolved somewhat. Institutional participation increased steadily since the late 1990s, fuelled not least by the first generation of CLOs. The securitisation implosion post-crisis saw part of this institutional buying power replaced by loan funds, some of which were listed. The CLO market comeback since 2014, and its solid growth in the past year especially (totalling €27bn since the beginning of 2017), has re-asserted securitisation as an important funding/ investment channel in the leveraged loan market. Currently CLOs account for around a third of the stock of leveraged loans outstanding, but that understates the degree of participation in new issues which stood at 38% in Q1 (compared to just 21% five years ago), according to LCD. Loan funds, whether listed or unlisted, are roughly equally dominant in their loan buying. Banks currently make up only 20-25% of high yield lending, with this disintermediation fuelled by a number of factors to include the more restrictive, US-like leveraged loan lending guidelines imposed recently by the ECB.

This degree of institutionalisation means that the capital market footprint of leveraged loans is sizable, not only as direct investments of course (not dissimilar to syndicated high grade loans) but also indirectly via CLOs and listed loan funds. CLOs dominate this footprint, with listed (equity or unit) funds being less ubiquitous relative to unlisted loan mandates.

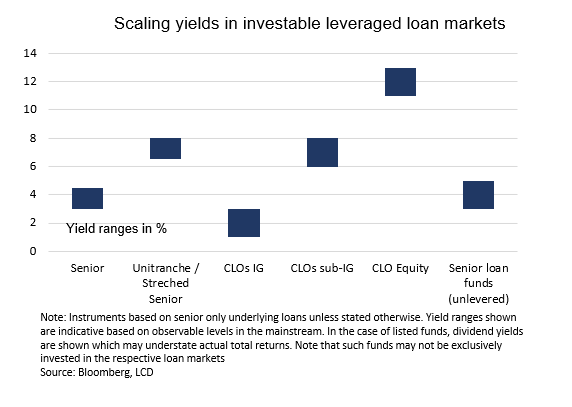

Notwithstanding the recent sell-off, leveraged loans and its constituent products such as CLOs have rallied significantly since the end of 2016, outperforming most other comparable traded credit. Currently, the yield universe ranges from very defensive senior CLOs to highly geared CLO equity, with loan funds somewhere in between in terms of yields/ returns. Senior AAAs currently have spreads around 70bp, while deeply subordinated BB/B yield in the range of 6-8%, with equity often returning in the low-teens. Listed senior loan funds yield in the range of 3-5% (not dissimilar to direct leveraged loan yields of course), with total returns enhanced over the past year by stock/ unit price or NAV appreciation. Unlike the US, such funds are generally unlevered, reflecting the capital incentives for the dominant end-investors, that is, insurance and pension money.

On the face of it – without analysing any structural and asset nuances – yields on highly geared CLO equity and/or retention tranches continue to be outliers in the context of overall loan capital market opportunities, much as can be expected. We would finally add that a number of ‘second order’ listed funds exists that invest in CLOs across the capital structure, including funds dedicated to deeply subordinated/ equity CLO tranches.

The direct lending revolution in mid-market loans

The mid-market loan space lacks the definition seen in large-cap and SME sectors, being almost by default neither of the latter two sectors. Like other loan markets, the mid-market sector has traditionally been dominated by banks, with institutional money crowding into the more liquid large-cap, leveraged loan market instead. However, the post-crisis era witnessed a notable shift in the balance of participants within the mid-market lending economy. Recent policy maker-led initiatives in various countries have also allowed better direct access to capital markets for mid-caps via private placement-like bonds, though borrower usage has been generally uninspiring. Examples include mini-bonds in Italy, Mittelstandsanleihen in Germany, MARF in Spain and the EuroPP programme in France.

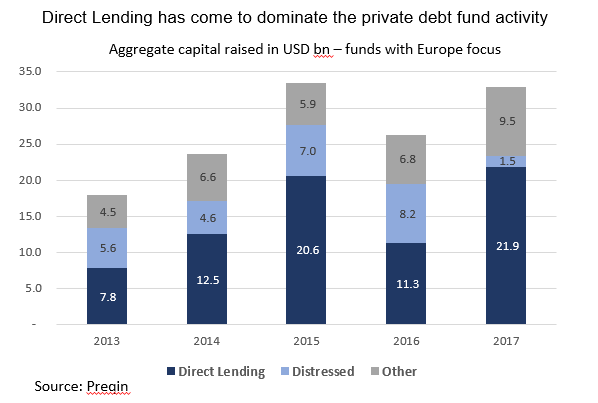

Non-bank institutions, made up mostly of asset or loan managers, entered the mid-market post-crisis as bank lending retrenched and disintermediation opportunities proved compelling. This evolution has been largely captured by the “direct lending” phenomena, led by the activities of private debt funds. Many of such funds are managed by traditional leveraged loan investors, with funds re-branded to target opportunities away from the capital markets, focusing instead on bank-facing borrowers. Such private debt funds have established a meaningful footprint in selected direct lending markets in Europe, particularly in the larger end of the mid-market loan segment, where deal flow channels share similarities with the leveraged loan market. According to Preqin, direct lending funds outstanding stand at €83bn (out of total private debt funds capital of €188bn) as at end 2017. In 2017 alone institutional direct lending mandates accounted for €22bn or two-thirds of all fresh capital raised by debt funds.

Proliferation of direct lenders has not translated into capital market opportunities

Direct lending styles, while varied, have generally tended to be imported from the large-cap, leveraged loan market i.e., where historically many such asset managers operate. For example, private debt funds are typically separated by sponsored and sponsorless lending, with the former resembling credit provided to private equity sponsors in a buyout or recapitalisation but in mid-market borrower situations. Such funds are also branded by loan types, with senior or unitranche loan funds distinguishable from mezzanine, special situations and/or venture debt, among other examples. Indeed, in many respects the asset profile of private debt funds within the mid-market space can not be perfectly defined, with lending practices generally fluid.

The commonly heralded theme with such funds is of course the disintermediation of traditional bank lending incumbents. But our take on institutional non-bank mid-market lending activity is that the theme has been less about outright disintermediation and more about complementing bank lending, that is, providing credit to corporates underserved by the banking system. Indeed, co-lending ventures between banks and institutional investors have arguably been most prevalent in the mid-cap space, typically via unitranche formats.

Securitised products have played little, if any, role in funding mid-market non-bank lending thus far. And with most direct lending funds being unlisted, there are therefore few capital market opportunities related to the mid-market loan space in Europe, certainly compared to the large-cap and SME markets. Unlike the US where the likes of BDCs have become established capital market conduits to mid-market loan investing, public listings of direct loan funds are still very rare in Europe for various reasons, among which we think are the challenges in deploying funds in this particular lending segment. (Case in point being that uninvested funds, or dry powder, among direct lenders amounted to just under €30bn – or more than a third of AuM – as at end 2017, according to Preqin). Similar to SMEs, the barriers-to-entry for non-banks are not insignificant.

From what we can tell the few listed direct lending funds that overweight mid-market opportunities typically have cash yields in the 4-7% region, though we would caveat that such returns may not be neatly attributable to the mid-market corporate loan market given the tendency to blend in other lending strategies. Among the large universe of unlisted direct lending funds, IRRs reported by selected investors in these funds (source: Bloomberg) indicate that returns range from ca. 4% for the more vanilla lending styles to as high as low double-digits for special situation lending where equity upside and deal fees typically enhance returns.

Marketplace lenders stand out as the disruptive non-bank entrants in SME loan markets

Banks still overwhelmingly dominate small balance or SME lending in Europe. According to the EBA, SMEs reliance on bank finance in Europe is up to 80% when including all credit formats (trade credit, leasing, overdrafts etc, aside from more vanilla lending), compared to just 25% in the US.

In our opinion, the continued dominance of banks in SME lending reflects the significant barriers-to-entry for non-banks, given both the extent of post-crisis central bank accommodation and even regulatory capital subsidies for SME lending as well as the legacy of inherently deeper borrower relationships and better credit intelligence within the banking system. But notwithstanding this asymmetric advantage, the post-crisis era has seen an appreciable degree of lending disintermediation under the circumstances, led mainly by direct lending funds and marketplace lenders. Early-phase capital for these funds have in some cases been provided by public bodies, in turn reflecting the highly politicised issue of SME credit availability, or lack thereof. (Examples include the Business Finance Partnership in the UK). Speciality non-bank lenders have also recently re-emerged (such fincos were far more visible pre-crisis), but for now remain too young to make capital market debuts.

Direct lending SME funds – less of a bang than headlines would suggest

Direct lending funds dedicated to the SME space remain few and far in between. Following a number of high profile launches in the immediate aftermath of the 2008/9 crisis, the growth of such SME funds stuttered over the ensuing years, all things considered. We think the challenges in deploying capital within the SME borrower markets was a key hurdle to the proliferation of such funds, moreover before long the incumbent banks were re-motivated to lend by central bank funding and other government/ supra-led incentives. A number of private debt funds formed co-lending partnerships with incumbent bank lenders as a means to source assets and provide alternative, yet complementary, financing to bank funding. Nearly all such SME direct lending funds are unlisted vehicles. There is little data to reliably highlight the extent of direct lending penetration of the SME markets, but data from the British Business Bank suggests that, in the UK, direct SME lenders accounted for less than 1% of total gross lending in 2017.

Marketplace lenders broaden the investable product suite in SME loan markets

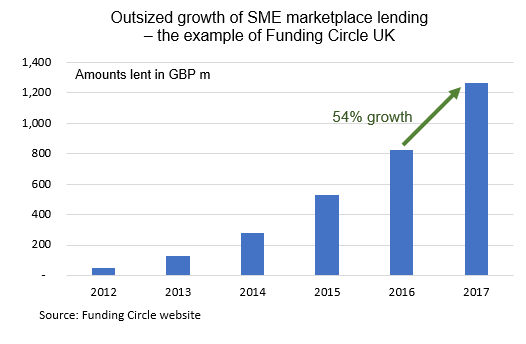

In somewhat of a contrast to the measured pace of growth of direct lending funds dedicated to the SME markets, marketplace lenders look to have made a greater impact if measured by the recent growth of origination volumes. Such lenders have long evolved from the retail P2P model, with the more established platforms currently serving as conduits for institutional whole loan investments, similar to trends in the US market. Selected marketplace institutional investors have listed equity funds. Such funds normally employ leverage to enhance returns, including in few cases tapping the public ABS capital markets. That aside, the marketplace platforms themselves of course provide channels to directly access SME credit in whole loan formats. Taken as a whole therefore, the growth of marketplace lending has broadened the suite of SME-related investment opportunities decisively, whether via whole loan or capital market instruments.

The marketplace lending phenomena has hitherto been limited mostly to the UK, although their growing presence – albeit still embryonic – in Europe is notable. Within the UK SME market, such lenders have originated £4.8bn of loans cumulatively since inception (source: AltFi), impressive in itself but still only a fractional penetration (3.3% of gross lending in 2017) of what remains an overwhelmingly bank dominated market. We would note that in the case of SME marketplace activity, the constituent base remains heavily concentrated for now, with the largest platform in the UK – Funding Circle – accounting for 70% market share of fresh lending since inception. Outside of the UK, total marketplace SME origination volume in Europe stands at €588m, but similarly one lender (Lendix) commands a market share of around 30%. (Source: AltFi). These concentrations highlight that marketplace disintermediation in SME loan markets is barely an industry theme and more a case of the dominance of one or two platforms.

Lending channelled via such technology-based platforms have tended to be in unsecured format for a number of reasons that have, conversely, underpinned their origination achievements, in our view. Unsecured lending lowers transaction costs relative to taking security and allows for a speedier loan underwriting/ approval process while also enabling lenders to tap borrower demand from SMEs without financeable collateral, which is precisely the pocket of the market where the banks have largely retreated from. (Secured SME lending is still a bank staple lending product). Higher yields on unsecured lending is in turn more appealing to the alternative whole loan investor base that dominates funding via such platforms.

Aside from the unsecured aspect, higher yields are also (arguably) justified by the premium for speedy loan approvals and smaller ticket sizes. But, marketplace loan yields remain significantly outside bank lending equivalents. Taken in combination with the explosive growth of such lending, there are naturally certain concerns around this model, as outlined below:

- The potential for adverse selection (particularly in cases of bank or broker referrals) in combination with a different skin-in-the-game model

- Credit scoring methodology which is not fully disclosed given IP issues, although there certainly is transparency and depth to the default and loss statistics

- Risks related to the concentration of the full origination-underwriting-servicing-workout chain under one roof, based on a (mostly) flat annual fee structure, particularly in the event of an economic downturn

- Other potential vulnerabilities of this still novel model as the industry matures. (The older US market has been witnessing such platform-specific challenges in the recent past).

Any such deeper analysis on the marketplace model is outside the scope of this commentary but we will address these concerns in a forthcoming report. However, suffice to say for now that P2P/ marketplace platforms look to us to be a near-perfect version of the originate-to-distribute model, and we would make the further important observation that these models are not lenders but conduits matching whole loan investors with borrowers. (Skin-in-the-game is therefore not as straightforward a consideration as it would be for other speciality finco lenders). Suffice to say also that the marketplace industry has thus far been unique in establishing a meaningful non-bank lending footprint in UK SME markets, much more so than any other post-crisis disintermediator model.

Asset-backed bonds dominate the SME capital market, but deal flow remains lacklustre

Securitised products make up a significant part of the investable footprint within SME capital markets, though such opportunities are noticeably smaller today relative to the pre-crisis market. Headline outstanding SME ABS volumes from banks of nearly €80bn (and €12.7bn in 2017 alone) vastly overstate the extent of investable opportunities given that most deal flow is retained for central bank repo funding purposes. Much of the outstanding market comprises legacy securitisations, with post-crisis new issue flow being relatively limited. (Only € 500m of SME ABS was placed in 2017). What little primary deal flow there is has been generally limited to senior (AAA/AA) bonds only, with very few securitisations placing mezzanine or subordinated paper.

Not that SME securitisation incentives have otherwise been lacking – there have been a number of initiatives both at national and EU-wide levels (ESIF/ EIF-led programmes for example) aimed at incentivising SME securitisations as a means to revive credit supply, while the ECB’s ABSPP has a well-publicised mandate as a ready buyer of such securitisations. But unlike similar programmes during the pre-crisis period that had their intended impact of generating deal flow, such as the ICO-sponsored initiative in Spain and the Promise programme in Germany (both since fallen by the wayside), these post-crisis initiatives have largely failed in resurrecting SME securitisations. Fact is, securitising SME loans for funding purposes is less cost effective for banks compared to other assets such as residential mortgages, on account of higher clearing spreads and less levered capital structures (i.e., more expensive credit support) – that aside, central bank special facilities (such as the TFS in the UK, repo window at the ECB) have acted as compelling alternatives to capital market funding by banks. Non-banks, to include marketplace platform investors for the most part, have brought a few SME securitisations to market, but such deal flow is limited at this stage. In contrast to asset-backed funding activity, SME loans have tended to be the asset of choice in regulatory capital relief deals, as we touch upon below.

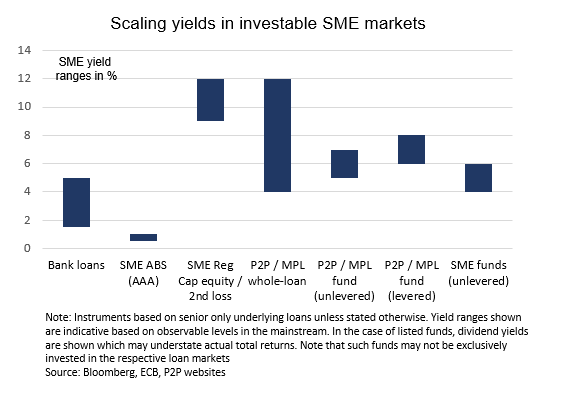

Except for reg cap trades, yield opportunities look most convincing in non-ABS formats

Counter-intuitively almost, the SME loan market enjoys a greater investable footprint than the mid-market loan space, thanks largely to bank-issued asset-backed bonds as well as the suite of opportunities presented by marketplace platforms, complemented by a few SME direct lending funds.

In terms of returns, senior bank SME ABS would typically be around the L+30-40bps range, with newer alternative portfolios (to include marketplace loans) priced appreciably wider. To the extent observable, listed direct lending funds yield in the range of 4-5%, mirroring margins in the underlying alternative SME loan markets. Funds invested in marketplace loans generally offer higher yields, reflecting fund-level gearing in some cases aside from typically higher loan-level spreads. Indeed, marketplace SME whole loans come in a wide range of yields from 4% in the case of defensive lending to as much as 15% for riskier assets, with the bulk being in the 6-12% range. As we mentioned earlier we are not taking into account yield risks in this commentary, but the consideration is important in the case of marketplace unsecured loans given the naturally higher losses-given-default, compared certainly to large or mid-market secured lending.

We remark finally on regulatory capital trades, many of which reference bank SME loan collateral. According to SCI, placed reg cap tranches totalled around €14b across 36 trades in 2017, highlighting that this esoteric market has a far greater footprint compared to vanilla, senior-stack SME ABS. Most reg cap trades are privately placed but the very few public deals – and data on returns from listed reg cap funds – suggest that yields on such highly levered, first/second loss tranches can range from the low double-digits and upwards. But we would caveat that these instruments are not priced to asset finance yields but rather to the economics of regulatory capital relief provided to the hedging banks.

More non-banks in the credit economy = deeper alternative lending markets = greater scope of investable opportunities

We see the investable, capital market universe related to European loan opportunities growing in the coming years, based on the following arguments:-

- Policy makers, whether under the guise of CMU or otherwise, seem committed in some ways to lowering the barriers of entry for non-banks in the credit lending system. (In the UK, for instance, banks are obliged to refer declined borrowers to alternative lenders). That aside, a number of funding-side initiatives – to include fund capitalisation and debt buying programmes – have yet to fully take effect, and could ultimately better anchor the non-bank credit economy in Europe

- One particular barrier related to proprietary borrower intelligence enjoyed by the banks is likely to be undermined by the PSD2 directive (plus the Open Banking Standard in the UK) – in effect, non-banks should gain some of the asymmetric information advantage of incumbent banks as SMEs can more easily share their bank data, which is of course more timely and potentially more credit instructive than statutory accounting data

- Absent a macro shock, better technicals in the securitisation market should create deeper economic funding outlets for non-banks, whether CLO managers, marketplace investors or newer speciality fincos. (The latter being distinguishable from CLOs by their originate-to-distribute rather than asset management model). In the case of SME asset-backed markets especially, securitisation regulation – STS in particular – could potentially fuel stronger demand for SME ABS

- Still, central bank accommodation of corporate (SME especially) loan funding to banks remains exceptionally generous, though potentially there will be tapering in the foreseeable future (or already being withdrawn, in the case of UK). We would expect banks to continue re-intermediating mainstream lending to corporates but still see a meaningful role for non-banks in selected pockets of the lending market. Such alternative lending should deepen as the economic recovery matures.

Overall, we expect securitised bonds to continue dominating the investable landscape, but with listed fund opportunities (including geared vehicles) increasing in scope. To be sure, Europe would see a transformational impact on non-bank lending and investable opportunities if it were to introduce US BDC or REIT-like legislation that institutionalises the non-bank credit system.

Disclaimer:

The information in this report is directed only at, and made available only to, persons who are deemed eligible counterparties, and/or professional or qualified institutional investors as defined by financial regulators including the Financial Conduct Authority. The material herein is not intended or suitable for retail clients. The information and opinions contained in this report is to be used solely for informational purposes only, and should not be regarded as an offer, or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell a security, financial instrument or service discussed herein. Integer Advisors LLP provides regulated investment advice and arranges or brings about deals in investments and makes arrangements with a view to transactions in investments and as such is authorised by the Financial Conduct Authority (the FCA) to carry out regulated activity under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA) as set out in in the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Regulated Activities Order) 2001 (RAO). This report is not intended to be nor should the contents be construed as a financial promotion giving rise to an inducement to engage in investment activity.Integer Advisors are not acting as a fiduciary or an adviser and neither we nor any of our data providers or affiliates make any warranties, expressed or implied, as to the accuracy, adequacy, quality or fitness of the information or data for a particular purpose or use. Past performance is not a guide to future performance or returns and no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made regarding future performance or the value of any investments. All recipients of this report agree to never hold Integer Advisors responsible or liable for damages or otherwise arising from any decisions made whatsoever based on information or views available, inferred or expressed in this report. Please see also our Legal Notice, Terms of Use and Privacy Policy on www.integer-advisors.com