Private credit opportunities across consumer, mortgage and SME alternative loan markets

![]() UK Specialist Lending Opptys_Integer Advisors 04 Jun 2019 (PDF Version)

UK Specialist Lending Opptys_Integer Advisors 04 Jun 2019 (PDF Version)

Executive summary

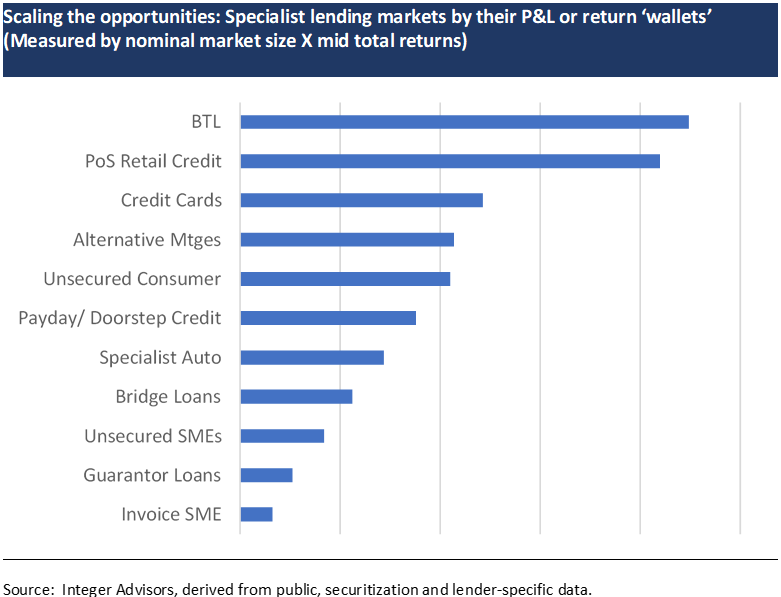

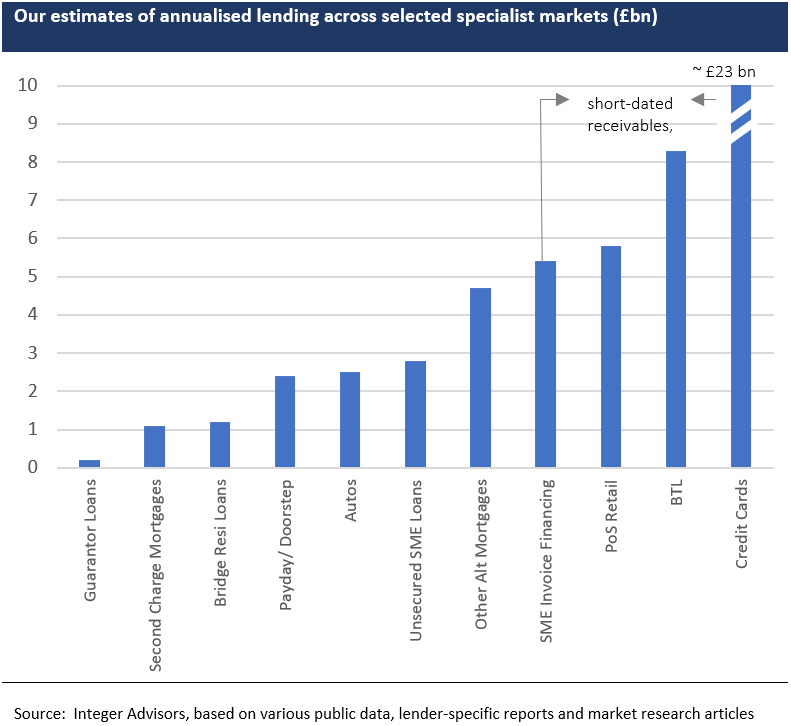

In this report we focus on investable opportunities in the UK specialist lending markets, across the consumer, mortgage and SME sectors. ‘Specialist’ lending can be generally defined as lending related to non-prime borrowers and/or non-conventional loan types, and by definition sits mostly outside of the mainstream banking system. The UK is distinct in being characterised by a relatively deep and diversified alternative loan market, unlike any other European credit economy. We estimate the size of this alternative lending market is around £100bn in terms of outstanding stock, or around 6-7% of the total loan market.

Recent growth of the UK specialist lending market stems equally from the post-crisis bank disintermediation opportunity as well as the sizable captive audience of “underserved” borrowers, which in turn reflects the relatively narrow lending remits of mainstream bank lenders. Looking across the lender, borrower and loan type continuum in this niche credit ecosystem, we would note the following: –

- Lenders are a mix of challenger banks typically with narrower lending styles, non-bank specialist fincos, P2P/ marketplace platforms and even institutional asset management-based direct lenders. Among the non-bank constituency, origination and servicing (including workouts) are sometimes outsourced. Many models – beyond P2P/ marketplace platforms – have also embraced digitization in recent years, in terms of the lending interface, underwriting and borrower relationship management

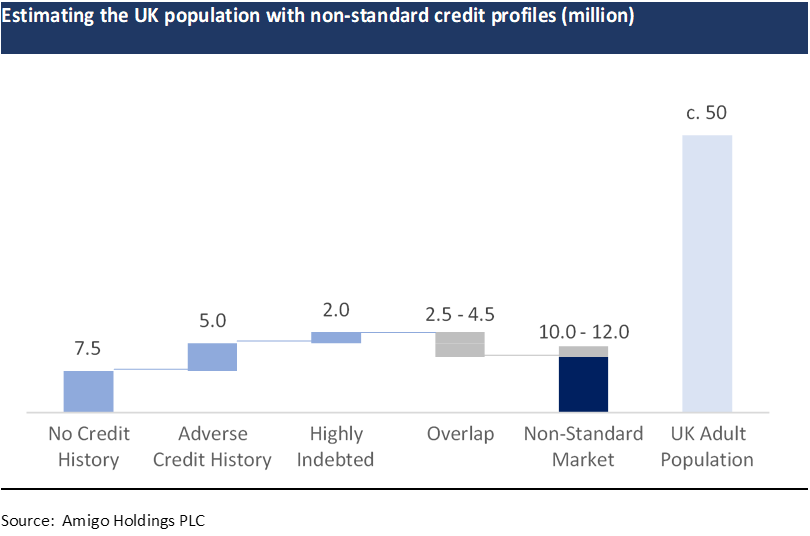

- Borrowers sourcing credit from specialist lenders are those with non-mainstream credit profiles. For the most part, such borrowers generally have thin/ no credit history, or are credit impaired / adverse given past uncured delinquencies, or are considered non-standard for other reasons (low income, self-employed, inconsistent address history, etc). Alternative borrowers can also include the highly indebted, whether household or small business

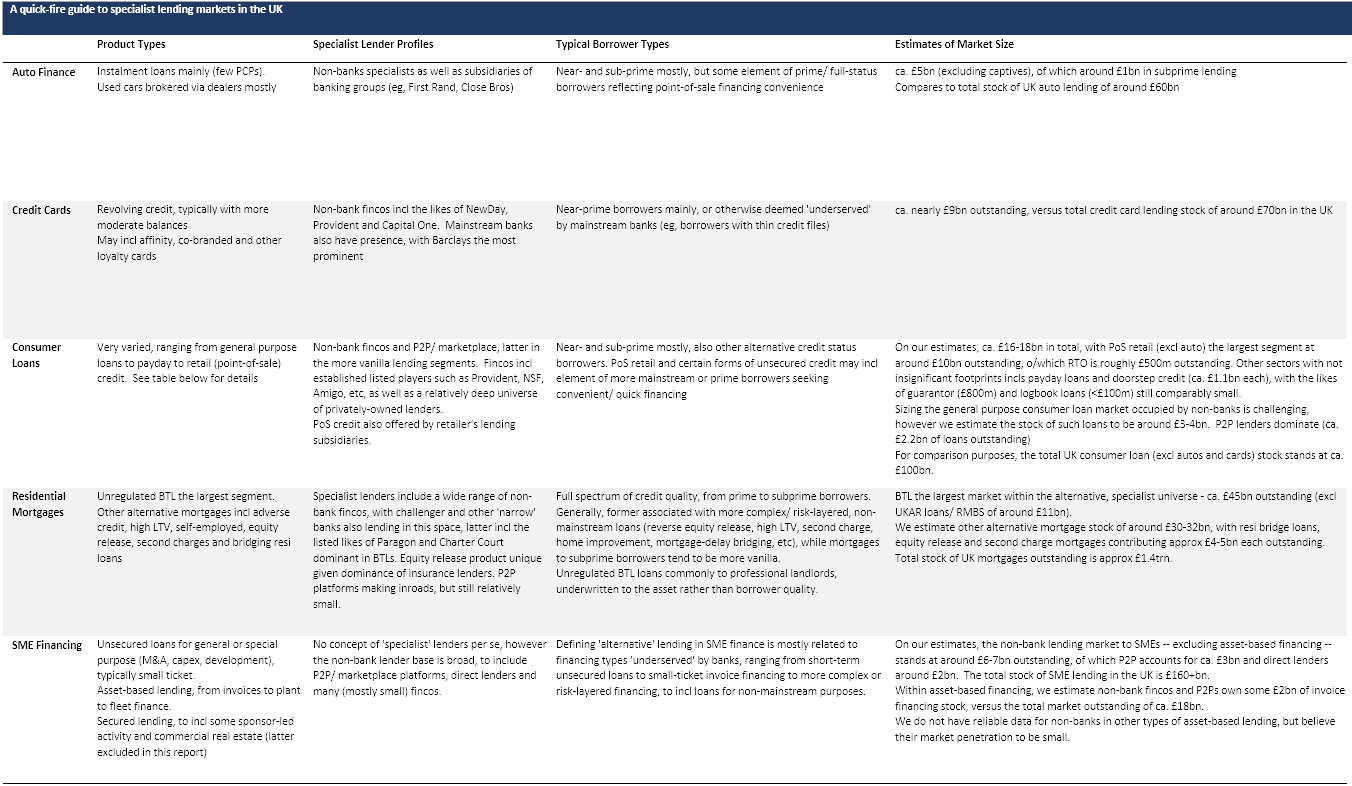

- Loans originated within the alternative space would typically be ‘off-the-run’, whether for reasons of complexity, risk-layering and/ or non-mainstream use of proceeds. In the SME market, specialist loans tend to be characterised by small ticket, unsecured credit.

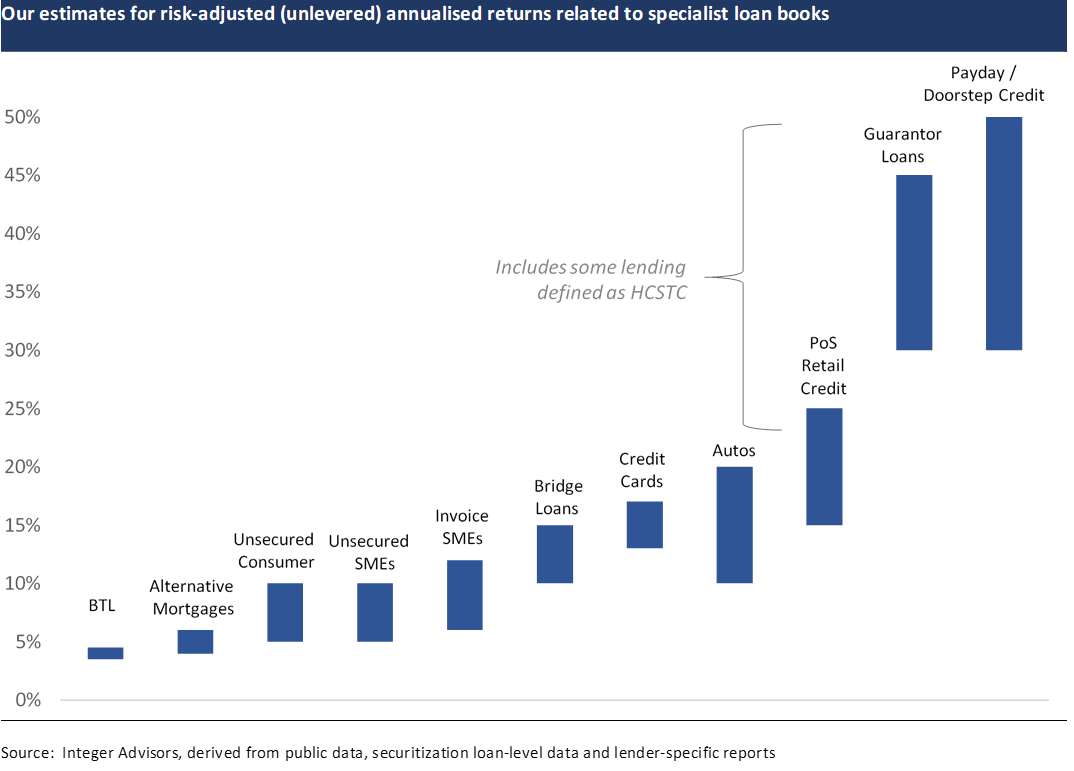

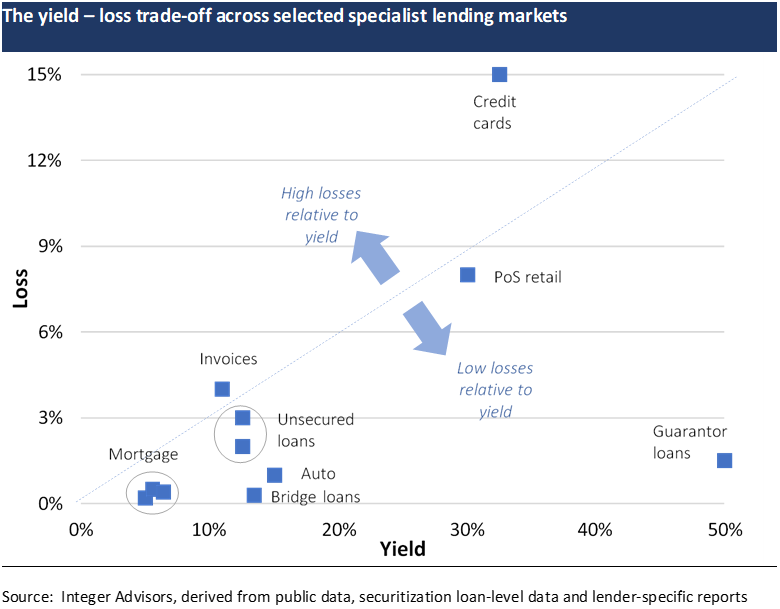

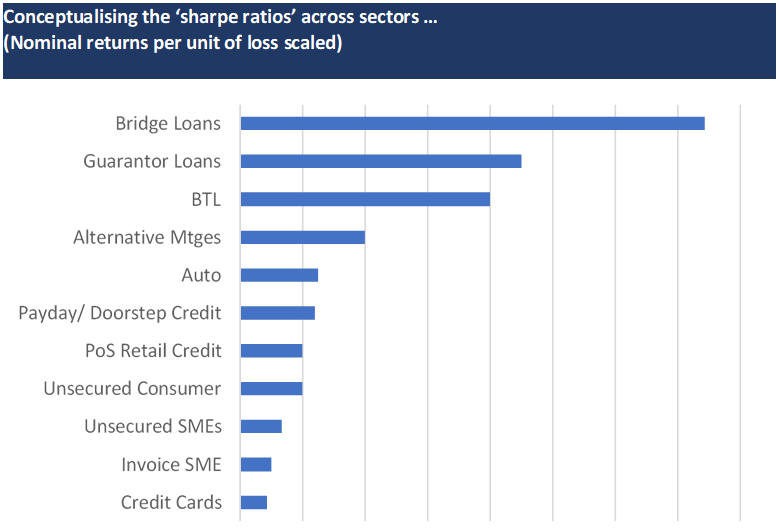

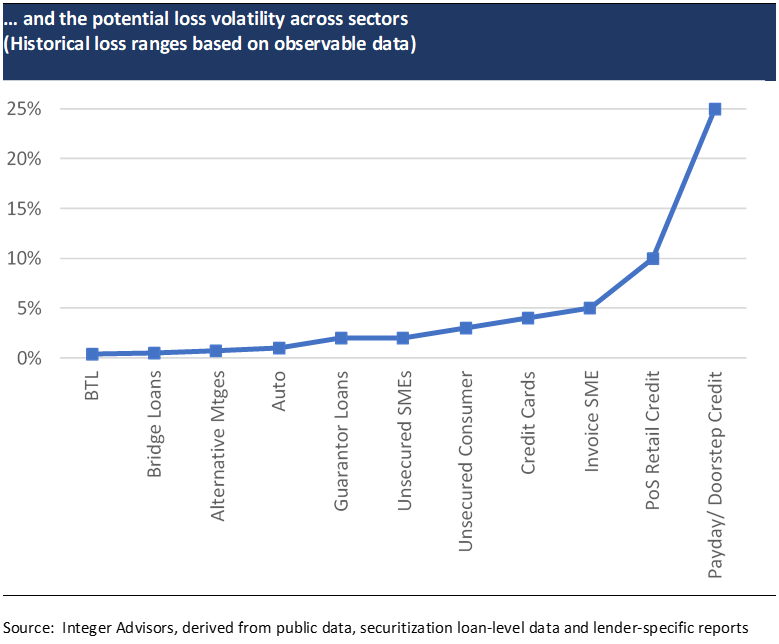

In scoping the potential private credit opportunities related to UK specialist lending, we use an approach that isolates such whole loan asset portfolios. Our analysis finds that unlevered loss-adjusted annualised total returns in these specialised lending opportunities can range from the 4-6% area in the most credit defensive end of the lending spectrum, namely specialist first charge mortgages, to ca. 10-15% in the more established consumer and SME lending markets such as autos, credit cards and unsecured loans, to returns in excess of 35% for very specialised, high cost consumer credit such as payday or doorstep loans. (In the case of the latter, we caveat the variability to such returns given potential loan loss / dilution volatility). We also find that selected sectors – such as residential bridge financing and guarantor loans – look undervalued versus their immediate peers given lending yields that seem rich relative to impairments experienced over the recent cycle.

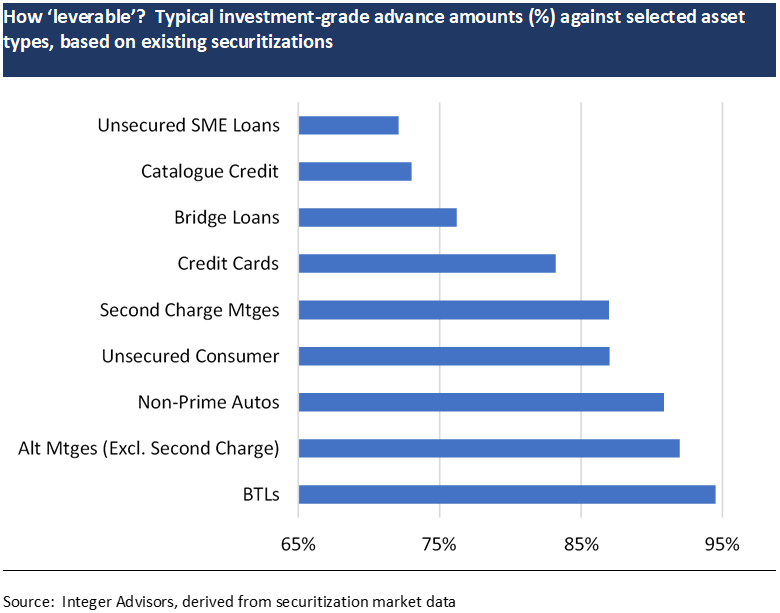

Many loan types within the specialist lending space are inherently leverable. Such readily available gearing can provide enhanced returns for loan book (equity) owners, allowing even the most credit defensive lending types – which are typically the most leverable – to generate above-normal total returns. Leverage also of course provides the debt investment channel into specialist lending opportunities, whether via public securitized markets or private facilities (direct secured financing, future flow funding agreements, etc).

However, existing investable capital market opportunities related to UK specialist lending – whether listed lender stock, bonds or securitized products – do not seem to fully capture the loan book return economics outlined above, unsurprisingly given the liquidity premium implicit in such instruments, not least. (Certain risk assets – such as high yield or securitized bonds – look cheap versus traded comparables, however). Private market alternatives such as whole loans (via marketplace platforms) and managed loan funds appear better yielding in this regard. Among the latter, which tend to provide the most diversified exposure into specialist lending, we see the unlisted, PE-style fund opportunities as generally more compelling versus the listed fund (closed-end investment trust) equivalents. In theory at least, unconstrained funds should be the most nimble in being able to exploit these private markets across debt and equity opportunities.

Total returns from investing in specialist loan books (hypothetical as the case may be) look appreciably superior relative to ‘traditional’ forms of private credit, namely direct corporate lending. Moreover, there is little evidence that there has been any meaningful slippage in underwritten credit quality within the specialist lending markets, in contrast to direct corporate lending in which loan gearing and covenant protections have deteriorated in recent years, as widely documented. But on the flip side, private corporate debt – particularly in the large cap, sponsored space – is more readily accessible by institutional money, whereas specialist lending is of course harder to reach. For this reason, we think alpha generation among alternative credit funds invested in specialist lending markets has more to do with being able to originate these opportunities than it is just stock-picking

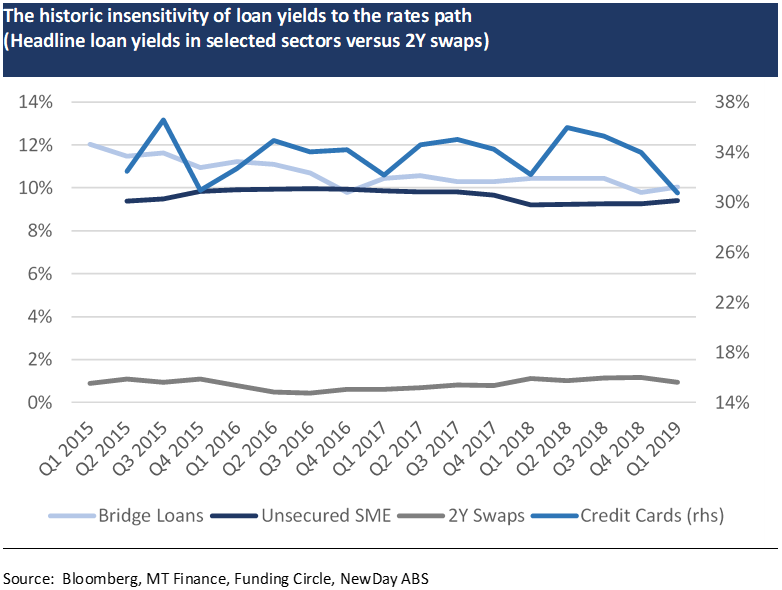

In our view, the key risks going forward, in terms of loan yield and origination resilience, comes from further regulatory reforms on the one hand, and lending competition on the other. Legislative changes can forcibly regulate loan margins and narrow the origination bandwidth via tighter lending standards, outcomes that already have precedence in the high-cost lending sectors. And what feels like the lack of competition in some segments of the industry today looks particularly susceptible to any reintermediation by mainstream banks, which could not only supress lending yields but also force specialist lending incumbents into more niche and/or riskier lending. (There are early signs of just such reintermediation in parts of the first charge mortgage markets, while bank online “flanker brands” are making inroads into other lending sectors). Credit performance over the longer-term horizon would likely be negatively influenced by any such drift into a riskier product mix, as it would of course under any fundamental deterioration in economic variables such as employment, disposable incomes or house prices. Notably however, unlike most other risk assets, we do not see specialist lending markets as being materially vulnerable to any normal shifts in interest rate paths going forward.

[All data used in this article – unless stated explicitly otherwise – is sourced variously from different public official sources including the FCA sector-specific reviews, securitization and P2P data, statutory reporting by listed lenders/ loan funds as well as other market research sources. Please contact us for more details and/ or further market insights derived from our data research]

Profile of the Alternative Lending Markets in the UK

Genesis of this niche lending system

Alternative lending in the UK has no precise or standardised definition that we know of, with the terms specialist lenders, alternative finance and underserved borrowers often used interchangeably in describing the full reach of lending activity within the sector. For purposes of this report, we look at lending that is characterised by non-prime borrowers and/or non-conventional loan types, outside of the banking system and mainstream loan markets. While this definition is by no means perfect, we believe it captures the bulk of activity in the alternative lending, and ultimately institutionally investable, space.

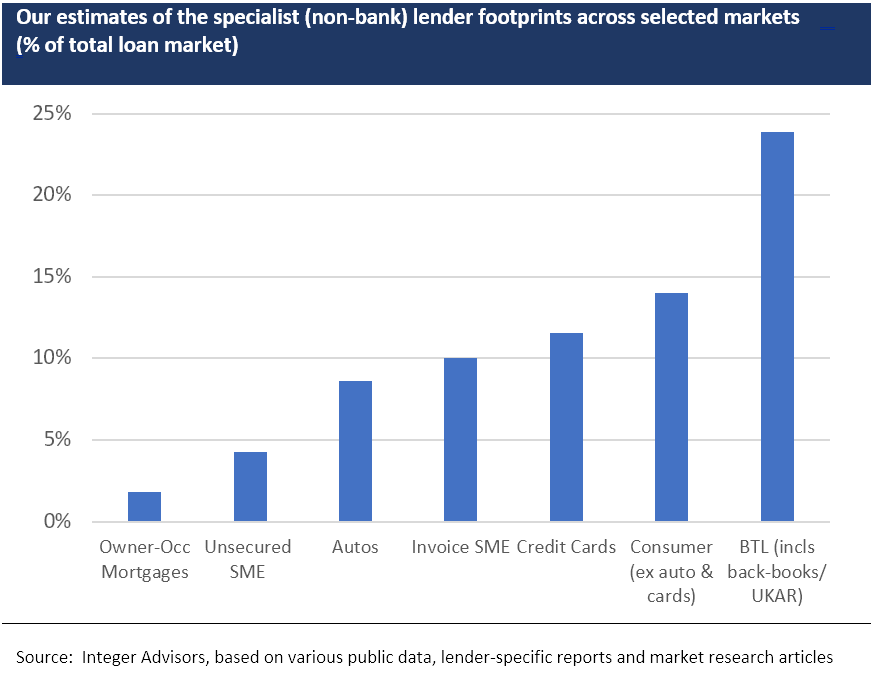

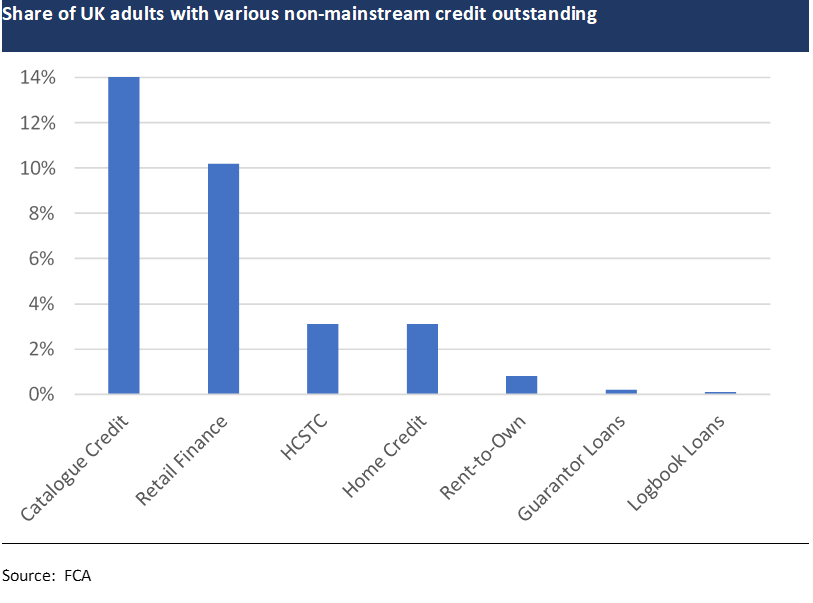

We estimate the size of this alternative lending market is around £100bn in terms of loan stock, with mortgages (unregulated buy-to-let products mainly) comprising the bulk of this footprint. On our estimates, this roughly equates to an alternative, or specialist, lending footprint of around 6-7% of total loan stock across the consumer, mortgage and SME markets. Various estimates put the likely population of ‘alternative’ borrowers – defined as having non-mainstream debt outstanding – at between 10-12 million people, or some 20% of the UK adult population.

The UK is distinct in being characterised by a relatively diverse range of loan types within the alternative credit space. Whether unregulated BTL or payday/ doorstep credit or alternative finance for small businesses, the UK alternative lending market is arguably the deepest and most mature among any in Europe, dating back some 30 years to the onset of financial sector liberalisation in the 1980s. Among developed economies, we feel only the US is characterised by a greater degree of specialist, non-bank lending.

Notwithstanding the established, decades-long momentum in the UK alternative lending industry, a number of key factors has served to reshape such markets over the post-crisis era, namely:-

- More onerous capital requirements and risk governance on established mainstream banks, which led to narrower and more regimented lending remits, in turn fuelling greater disintermediation opportunities for the likes of non-bank, alternative finance providers. Banks effectively pulled out of any ‘stretched’ lending into consumer and small business sectors, with such attrition compounded by the complete withdrawal by many foreign bank lending subsidiaries

- Reduced role of securitization as a capital market outlet, which not only proved destructive to many originate-to-distribute finco models in this space but also fuelled newer formats of ownership and funding among the private specialist lenders that survived the crisis. This gap was largely filled by alternative institutional investors – PE, for the most part – that have provided fresh equity and debt financing (whether via direct facilities or forward flow agreements, etc) to many specialist lenders

- Greater regulation across many aspects of this ecosystem, from lending and underwriting standards, borrower protection, capitalisation, securitization etc which has influenced everything from lending styles and target borrower markets to funding and capital considerations, not to mention the very survivability of a number of lending models. We expand on regulatory reforms later in this article.

Lenders in the UK alternative lending space have historically been led by a constituency of finco originators simply called “specialist lenders”. Over the post-crisis era, such lenders have comprised larger, listed players as well as private fincos, often originate-to-distribute models seeded or funded by alternative/ PE investors, as mentioned above. Selected challenger banks with narrow, specialist lending styles have also emerged in the post-crisis period, as have online lenders such as P2P/ marketplace platforms, arguably one of the most notable developments in alternative finance in recent years. Institutional asset management-based direct lenders have also become more noticeable in the SME financing space than at any time in the past, though their lending activities tend still to be weighted more into larger corporate (often sponsored, leveraged) lending.

Save for the larger fincos and online platforms who enjoy direct borrower channels, most other speciality lenders originate loans via the established broker networks in the UK. (In the case of certain HCSTC markets, intermediaries called “lead generators” are also used to source product). Loan servicing and workout management are also commonly outsourced to third-parties, leaving many speciality lenders with funding and portfolio management responsibilities largely. Specialist lending has seen increased digitization in recent years, with online lending interfaces becoming very much the norm.

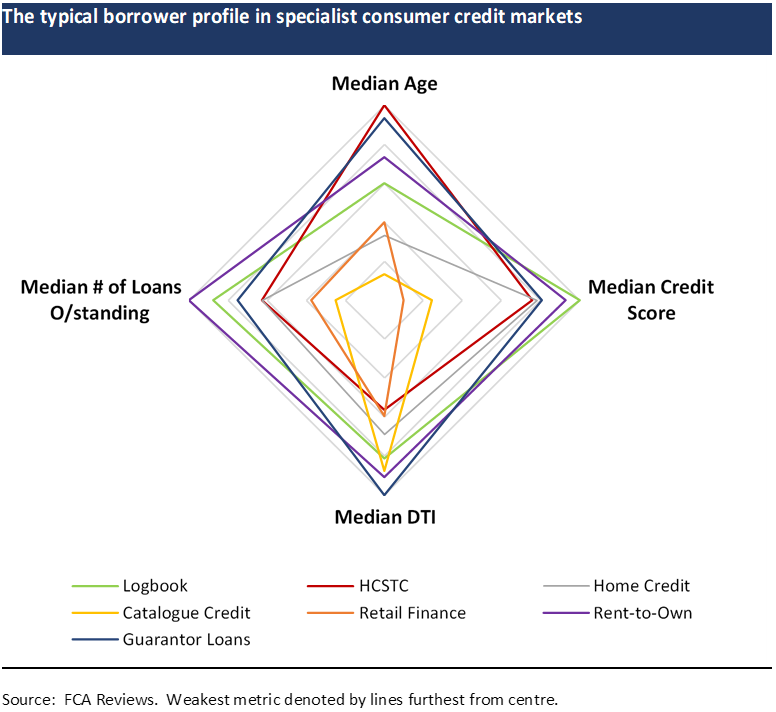

Borrowers in the specialist lending market are characterised typically by non-mainstream credit profiles. This could span thin or no credit history, credit impaired / adverse given past uncured delinquencies, or non-standard credit status for other reasons (low income, self-employed, inconsistent address history, etc). Alternative borrowers can also include the highly indebted, whether household or small business, and borrower seeking financing for non-mainstream purposes.

Loans originated within the alternative space are normally ‘off-the-run’ by nature, that is, products that are generally more complex and/ or risk-layered. We see a trade-off of sorts with borrower credit profiles in this respect, meaning that the more layered such loan products are, the more mainstream the borrower is likely to be. In other words, a subprime or credit-adverse borrower would likely only be eligible for a standard loan from an alternative lender, whereas a prime/ near-prime borrower could avail more complex products (high gearing, speculative loan purposes, etc).

Recent market growth and the impact of regulatory reforms

The market for alternative lending in the UK has experienced relatively steady growth overall in recent years, following the sharp contraction in the aftermath of the crisis. But growth has been uneven across the different sectors, indeed the overall observation masks somewhat divergent trends in individual markets. We would make the following notable observations: –

- Car finance in the alternative space experienced sharp growth up to 2016/17, prompting concern and greater oversight from macro prudential regulators. Growth has moderated more recently

- Unsecured personal loans – and especially point-of-sale retail credit – has also seen above-trend growth recently. By contrast, the likes of payday loans and doorstep credit – and indeed any lending that has come to be defined as ‘High Cost Short-Term Credit’ or HCSTC – have moderated in volumes, with greater regulatory oversight as well as better consumer credit literacy in recent years taking a toll on both lending and borrower demand

- Unregulated buy-to-let mortgages have also witnessed weakness in lending volumes in recent years since the sharp spike in the run-up to the new tax regime in early 2016, with macro factors and the fiscal disincentives weighing on the market more recently

- Alternative mortgage types such as residential bridge loans, second charge mortgages and equity release products have seen relatively strong growth in recent years, fuelled largely by household demand to realise value locked in home equity. Second charge loans have seen particularly strong growth recently, up 20% yoy in February 2019, according to EY

Growth in alternative SME financing looks to have been steady in recent years, however the availability of data (or even estimates) for this market is particularly challenging. From what we can tell, non-bank alternative lenders have noticeable footprints only in specialised markets such as invoice financing. In more vanilla (unsecured) lending where banks still dominate, the emerging role of P2P/ marketplace platforms in recent years has been notable, with such conduits accounting for nearly 10% of new SME lending flows (but still much lower in terms of the share of lending stock), on our estimates. Post-crisis rules requiring mainstream banks to refer declined SME credit to alternative lenders is a key driver of this emerging non-bank activity, in our view.

Regulatory reforms that have been rolled out in recent years are arguably the most significant factor shaping the market for alternative lending in the UK. Taken in its entirety, regulatory reforms in the post-crisis era have of course been wide ranging in their scope and aims, affecting lending activity across bank and non-bank/ alternative markets, to include mortgage, corporate and consumer lending. However, reforms to non-mainstream lending practices in the UK consumer credit market, in particular, have looked the most profound.

Consumer finance came under the regulatory net of the FCA from April 2014, prior to which the Office of Fair Trading was responsible for overseeing the compliance with the Consumer Credit Act, or CCA. The FCA supervision essentially covers all lenders and intermediaries, with the scope of regulations encompassing credit advertising, lending conduct and adequate transparency of loan terms (to include expressing lending rates as APRs) as well as debt management/ collection, among other practices. (The FCA rules, which reflect a principles-based regime, are enshrined in its Consumer Credit Sourcebook). Within the consumer finance space, credit agreements that are regulated are specifically lending to individuals (< £60,260) or sole traders/ micro partnerships (< £25,000).

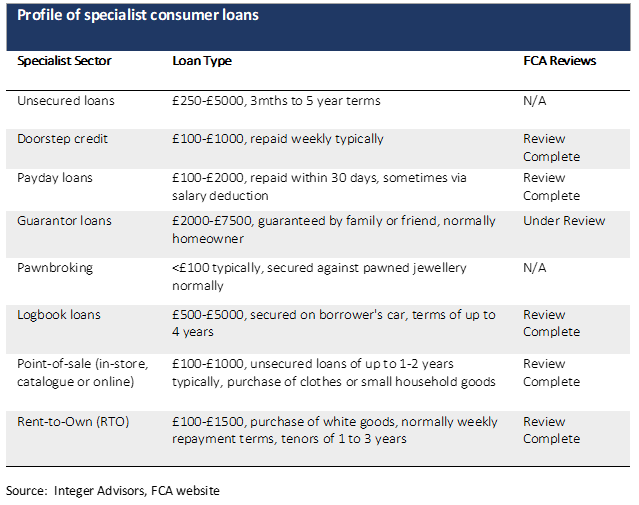

The most disruptive aspect of consumer finance regulatory reforms has been in the “HCSTC” sector, defined by the FCA as regulated unsecured loans less than one year in duration carrying interest at over 100% APR. Not all forms of HCSTC have come under greater regulation at this stage, only the likes of payday loans and certain types of RTOs. (Logbook loans – which falls under legislation governing Bills of Sales – as well as doorstep and catalogue credit are excluded from the rules, for now). The new regulatory regime for HCSTC, which came into effect at the beginning of 2015, is uniquely prescriptive. Aside from relatively comprehensive governance around responsible lending (including affordability checks) and product transparency, the new rules also feature economic limits on lending, namely:-

- Cap on interest rates (including fees) of 0.8% per day (nearly 300%+ on simple annualised basis). Further, default fees are limited to £15 per loan

- Overall total borrower costs (interest + fees) capped at 100% of sum borrowed

- Limits to loan rollovers of two times, with similar limits for lenders seeking continuous payment authority

- And in the case of RTO loans, new rules since April 2019 regulate pricing of ‘bundled’ goods sales (where the bundle includes insurance, warranties, etc), in effect capping the cost of the non-goods element at the cost of the goods themselves. Additionally, firms are required to conduct price benchmarking exercises to mitigate risks of overly inflating goods prices, often for reasons of subsidising credit costs.

The reforms have had far-reaching effects on the industry, not least on the scope of originations and lender profitability. (According to a CMA report, payday lender returns on capital were as high as 40+% in 2013 on the eve of the new regulations, falling sharply since then). Aside from shrinking the lender industry, the new regulations have also de facto shaped typical loan structures in the marketplace, in terms of rates, tenors and the amounts lent, as lenders have attempted to limit the regulatory impact or bypass the new rules altogether. However, the flip side of reduced lender profitability has been better default behaviour, according to anecdotal evidence. We see the reforms as also helping to cement the longer-term viability of certain forms of specialist lending, albeit at the likely expense of origination opportunities.

Dissecting Returns in the UK Alternative Lending Market

In this section, we analyse hypothetical total returns that can be derived from such alternative loan types, ahead of discussing current investable opportunities in these markets. We use an approach that isolates the whole loan asset portfolios. By this we mean looking at nominal yield and loss estimates related to typical loan books which are hypothetically carved out of the lender, in effect therefore net (or loss adjusted) portfolio income margins, which are of course distinguishable from opco equity returns. Where possible, we also adjust for any ancillary fee income that supplements loan book yields as well as operational costs related to loan portfolios (servicing and delinquency management mostly), with such cost estimates derived mostly from securitization transactions.

Sizing potential risk-adjusted loan book returns

On a wider observation, we would note that nominal loan book yields in specialist/ alternative lending markets in the UK are generally higher than the equivalent in most of developed Europe (currency unadjusted), and certainly versus the core EU credit economies, which remain heavily banked by comparison. However, relative to like-for-like alternative loan products in the US, lending yields look much less distinguishable, indeed in certain sectors (subprime consumer finance, for example), nominal loan yields in the US appear richer, unadjusted however for risks or the currency basis.

As we elaborate below, yields in the alternative lending space range from ca. 4-6% among the most defensive loan products (mortgages namely) to upwards of 100+% for very specialised, high cost consumer credit. Yields on most specialist loans and mortgages have been largely range-bound in the past few years. Notable exceptions however are the likes of payday loans, in which both lending rates as well as fees have been driven lower by the HCSTC regulatory reforms from 2015, not to mention pressure from consumer groups. Near-prime credit cards also stand out given portfolio yields that appear very sticky, having been mostly unchanged since the pre-crisis days. Our take on loss estimates over the past year or two in specialist sectors – sourced variously from FCA reviews, securitization and P2P data as well as statutory reporting by listed lenders/ loan funds – also highlights clear demarcations by lending types, which roughly mirrors loan yields

Coming now to total risk-adjusted returns related to (hypothetical) investments into such loan books. Total unlevered returns after losses tend to cluster into the three bands, in our view, described by their headline yield ranges and estimated loss experiences: –

- Starting with the most credit defensive end of the lending spectrum, investing in specialist mortgages – comprised of unregulated BTLs and other alternative products (adverse credit, high LTV, etc) – looks to generate total returns in the 4-6% range, with higher quality BTLs in the lower end of that range and the likes of second charge products at the upper end. Residential bridge loans are an outlier by most return measures, as we touch upon below. First charge mortgages typically yield between 4.5% and 6% including fees. Second charge mortgages usually yield 6.5% or higher, depending on risk profile. (All of these observations are corroborated by respective RMBS pool yields). Total returns are not far off such yields given the superior credit performance of mortgage products, where annual realised losses are typically no more than 0.4%. There has been little loss variability among mortgages over recent cycles. Residential bridge financing is a notable outlier, however. Lending rates of between 12-15% typically have little incremental losses, relative to other owner-occupier or BTL mortgage products, to show for it. Low losses in bridge loans are explained by the typically conservative LTVs among such products, averaging only 55% in 2018, according to MT Finance (and up from 45% a couple of years earlier). Bridge loans are also an outlier from a tenor perspective, being far shorter dated (< 18 months typically) than other mortgage types, which normally have weighted average lives of anywhere between 2 and 5 years, notwithstanding final maturities that can be up to 25 years. Second charge mortgages seem also to be somewhat undervalued by this same measure, albeit to a lesser degree

- Total unlevered investment returns in the bulk of established consumer and SME lending – such as autos, credit cards, unsecured loans, more vanilla point-of-sale credit and invoice financing – look to be in the high single digits to say around 15%. Better quality unsecured loans to households and small businesses tend to generate risk-adjusted returns in the high single digits, whereas the likes of near-prime auto and credit card lending fall in the 10-15% range, generally speaking. Durations for such assets range from the ultra-short, revolving types (cards, invoices) to term loans typically up to 2 or 3 years in maturity. The above findings are based on headline lending rates that fall mainly in the 10-20% range, with many such ‘mid-cost’ specialist loans originated by a wide spectrum of lender types, including P2P platforms. Near-prime credit cards stand out for their appreciably greater portfolio yields in in the 25-40% range, however such portfolios tend to exhibit higher charge-offs as well, typically in the 14-16% area. The more vanilla forms of unsecured consumer and SME financing can be shown to experience losses in the range of around 1-4%, with auto financing typically in the lower end of this range (subprime loans excepted).

- And finally there are the highly specialised consumer finance markets that are priced at 50+% yields (and often greater than 100% or even 200% annually). Such loan types include payday, RTO, doorstep credit, logbook and guarantor loans, many (not coincidentally) falling under the auspices of HCSTC as defined by the regulator. For the most part, borrowers in these loan categories are subprime (or ‘deeply’ adverse in some cases) in terms of credit scoring, rather than having non-standard credit statuses for reasons other than payment behaviour, as is sometimes the case of borrowers in other specialist lending markets. Loans in this category tend to be short-dated but can extend up to 3 years in tenor. Indeed, regulatory reforms put in place since 2015 have, by all accounts, fuelled a lengthening of loan terms as lenders seek to minimise the impact from the rules. In this higher-beta end of the market for specialist consumer loans, losses tend to vary relatively significantly – from around 5% of annual write-offs in the case of certain RTOs to nearer 10% for logbook loans and higher risk PoS financing to 40%+ for the likes of some payday and doorstep credit, in which of course lending rates are typically in the 100%+ area. Volatility around these ranges varies noticeably given what can be highly unpredictable credit exposures. Loss-adjusted total returns in such specialist consumer loans can (hypothetically) be in the 35%+ range, however as remarked above there is noticeable variability to such returns given loss variations as well as servicing costs, which may not be insignificant in such loan markets. Our observations are therefore academic for the most part. Moreover, the very small market footprints for some of these high cost credit sectors would arguably make them almost uninvestable for all intents and purposes, from the standpoint of institutional money. Yet, there are some interesting observations to make. Segments such as guarantor loans and certain RTOs, for instance, can be shown to exhibit impairment rates that are appreciably better than the broader sector, yet are based on lending rates that largely mirror the market (40/50%+ annually). The potential volatility around such losses notwithstanding, there is evidence to suggest that credit performance among such highly specialised lending sectors is much more uneven than otherwise indicated by the very high loan yield ranges.

The linear relationship between loan yields and expected losses is evident to some extent in the specialist lending markets, but as highlighted above, by no means is this correlation universal. Sectors such as residential bridge financing and guarantor loans look ‘undervalued’ against immediate peers, precisely given lending yields that look rich relative to low and predictable impairment risks over cycles.

An important caveat to our discussion above is the potential variability of underwritten credit risk and loan margins within any one specialist lending sector. While we feel the above analysis captures the bulk of loan profiles (or the ‘bell’ of normally distributed observations), loan credit quality and yields can vary – sometimes significantly – in any given sector, largely reflecting the different lender models and risk appetites. Take auto finance for instance. Subprime auto lending is characterised by markedly different risk/ return metrics than near-prime or other alternative auto loans, as highlighted in the recent FCA review of the sector. Loan rates of up to 40% are not uncommon in auto finance originated to adverse credit borrowers, but this only makes up an estimated 3% of total auto lending, according to the FCA. Conversely, not all specialist consumer loan markets such as payday lending or catalogue credit are priced at very high rates – there is equally a ‘tail’ of the market that caters to better quality borrowers (often seeking financing convenience instead of rate shopping), which carries yields that are more normalised. We would also highlight that specialist mortgage markets have very thin ‘tails’ in this respect (that is, there is very little outlying lending styles described by meaningfully higher loan risk/ yields), arguably given the widespread rules around underwriting standards based on affordability prescriptions.

The role of leverage in investment returns

The use of gearing in private loan markets is common, with opportunities in UK alternative lending no exception. Indeed, many asset types within specialist lending are inherently leverable, particularly of course the stable, fixed income-like loans, such as mortgages.

Leverage allows loan book (equity) owners to enhance returns. Such equity investments are typically represented – to varying extents – in managed loan funds, whether listed trusts or private unlisted PE-styled funds. Our proceeding discussion looks at hypothetical leveraged equity returns across different loan types, and is conceptual rather than scientific given that we are using a very broad-brush approach with one-size-fits-all assumptions. All we are doing is demonstrating that returns can be appreciably enhanced through leverage, adjusting the extent of gearing allowable by asset type so as to make the end-findings comparable.

In order to size the potential gearing quantum by asset type, we consider risk-constrained leverage – in this case we define the latter by the typical attachment points for investment-grade financing advances against each loan book type, which we derive from existing securitizations. (By definition therefore, gearing thresholds here are dependent on rating models for the respective asset types, which in turn will be influenced by a host of factors including credit resilience and performance track records, among many others). Our findings show – unsurprisingly – that the more credit defensive (or predictable) and established sectors, such as mortgages and autos, are generally more ‘lever-able’ versus the likes of unsecured SME or consumer credit. Assets such as BTLs or alternative first-lien mortgages, or indeed granular specialist auto loan pools, can be geared (using investment grade facilities) 10-15x, whereas the equivalent risk-constrained leverage ceiling for bridge loans or unsecured credit or specialist high cost consumer lending seems to be nearer 3-7x. Near-prime credit cards also fall in the latter category.

With such leverage, established sectors such as specialist auto loans look to generate among the most compelling total returns for equity positions in such loan books, notwithstanding the academic exercise herein. Even sectors such as BTLs can (hypothetically) generate equity returns into the 30%+ range with conservative extents of gearing. Our point here is that looking at risk-adjusted unlevered returns alone does not capture the full investment case. By exploiting leverage, total return differentials for equity between the more established markets and the high-beta specialised lending sectors (such as say payday or doorstep credit) look much less distinguishable. Employing leverage is not without risks of course, in effect gearing in this case involves taking incremental financial risk to get closer to high cost, high (credit) risk lending returns.

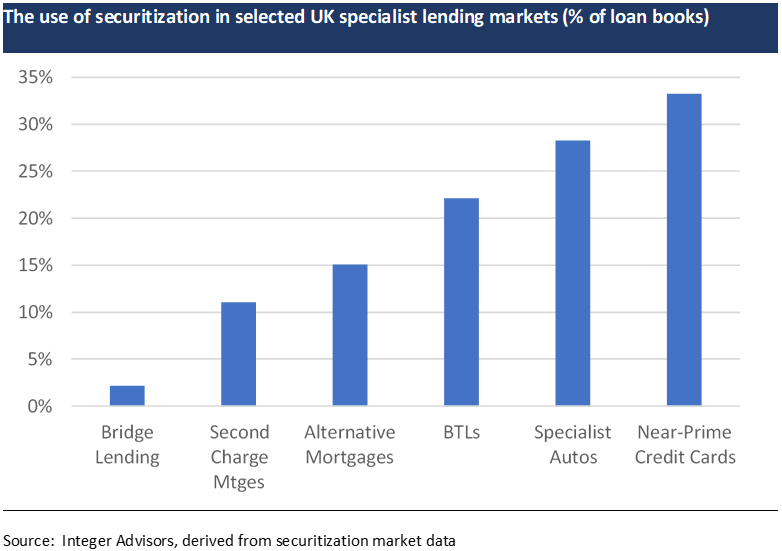

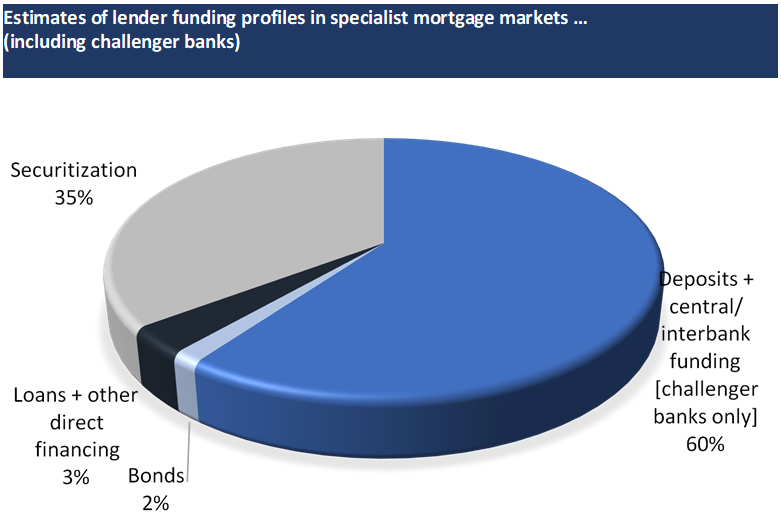

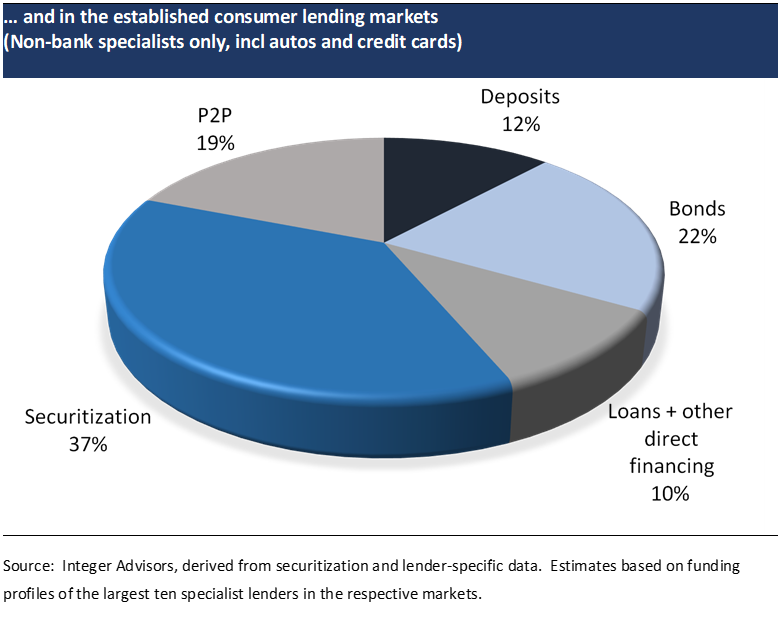

Leverage financing in itself of course mirrors the channels for debt investing into the specialist loan markets, which can range from public bond and securitization markets to private, often bilateral, facilities ranging from direct asset financing to forward flow loan purchase agreements. Within the former public markets, asset-backed securities tend to dominate, indeed the widespread use of securitization as a term financing / leverage outlet for owners of such loan books is testament to the leverability of these loan types.

Private financing agreements have become more common in recent years – from what we can tell such facilities are typically priced at appreciable spread pick-ups to public equivalent securitizations, which – judging from recent clearing spreads – typically equate to weighted average yields of 2.5-3.5% (depending on asset type) for the investment grade component of ABS/ RMBS capital structures

Understanding the risks to specialist loan book returns

Based on our simplistic analysis where annual loan book returns are a function of yield (and fee) carry less credit losses, it follows that any risks to such returns comprise factors that could potentially influence yields and/ or loss performance over the longer term. Among such factors, we would highlight the following:

- We think a key risk to loan yield resiliency – and indeed the sustainability of origination volumes – is the scope for further regulatory reform, which have already had an influential role in moderating lending rates and volumes in certain high cost consumer credit sectors. More regulation is still to come targeted mainly at the niche rather than established specialist lending markets

- Yet another key risk is the potential reintermediation of such markets by mainstream banks, fuelled – not least – by institutions that are generally flushed with capital trapped by contemporary ringfencing rules. This trend looks to be taking hold already in some parts of the first charge specialist mortgage market. Any lending ‘creep’ among specialist lender incumbents into riskier borrower markets, either because of such competition from deposit-takers and/ or other profitability pressures, could also of course shape the loss experienced by such lending in the future

- Unlike more mainstream loan markets, the path of interest rates can be shown to be a relatively insignificant influence on loan yields – which are mostly priced with significant headroom to rates – in all but the most defensive alternative lending segments such as first charge mortgages. For the same reason, we see the credit impact of any adverse interest rate shifts being limited mostly to mortgages (if at all) given both the typically long-term debt burdens and tighter relationship to base rates. By contrast, the high yield characteristics of most other alternative lending products, not to mention the typically high turnover (or short tenor) nature of such loans, arguably makes credit performance less sensitive to policy rates in any but the most prolonged or severe of tightening cycles

- Losses are of course vulnerable to cyclical downturns or shocks. A full analysis of loss vulnerability is outside the scope of this high-level report, however we would highlight employment and disposable incomes as powerful predictors of loan performance in most alternative consumer finance markets. (Indeed, an analysis by the BoE Financial Stability Report in June 2017 found a meaningful correlation between consumer credit losses and unemployment, lagged 12 months)

- Borrower “willingness-to-pay” is also an important consideration in terms of credit performance, particularly among the high cost consumer credit sectors. Non-economic factors are relevant in this respect, which can range in our view from cases of dissatisfaction with goods purchased via credit (to include examples of say loans secured against used cars or white goods) to other forms of strategic defaulting among high cost borrowers given lender failures and/ or changes in borrower behaviour towards loan rates seen as usurious or predatory. (As a case in point, complaints related to payday loans rose five-fold in the past year, according to Resolver, an independent complaints website)

- Losses can also be influenced of course by the quality of loan servicing and delinquency workouts at the lender or servicer level. The benign cycle recently has not provided any meaningful test of workout capabilities among the current breed of lenders, many of which only emerged in the post-crisis era.

Mapping Investment Opportunities in Tradable and Unlisted Markets

Institutional investment into UK alternative lending assets prior to the crisis was limited largely to securitization capital markets, whereas today the opportunity presents itself across listed stocks/ loan investment trusts and unlisted “opportunity” funds, whole loans (via marketplace platforms mostly) as well as securitized products and other debt types: –

- Listed equity opportunities are represented via the stocks of selected larger lenders as well as listed loan funds (or closed-end investment trusts, to be exact) managed by institutional investors. Listed loan funds typically invest in a broader array of opportunities via a mix of loans as well as securities, but – with a few exceptions – tend still to be bucketed by type, for example, online/ P2P loans or real estate assets or other single-sector exposures such as SME direct lending

- Securitizations of specialist loan books dominate the debt capital markets, especially of course in established lending markets such as mortgages, autos and credit cards. A few lenders also issue bonds directly, secured via floating charges over substantially all of the unencumbered assets of the lender – such bonds span low investment grade (sold into retail markets often) to high yield (institutional). Debt issuance in any form, which serve also as a leverage tool, tends to be limited to the more established lenders with sizable loan books and origination flows

- Whole loans feature as a newer investable channel courtesy of P2P/ marketplace platforms, the vast majority of which emerged over the post-crisis era. Such loans tend to be in specific sectors such as SME or consumer or property lending, with platforms having a more diversified product suite being rarer

- Unlisted institutional funds, often structured as locked-up, PE style vehicles. Investments by managers in this regard can include debt (whole loans, asset financing, etc) and equity (loan book residuals and/or stakes in fincos). For the most part, investments in UK specialist lending among such unlisted funds are part of broader private market strategies, commonly carrying such brands as alternative or tactical opportunities, principal finance, and so on. We only know of a very few select funds that are dedicated to such specialist lending markets.

Investable capital market opportunities related to UK specialist lending – whether listed lender stock, bonds or securitized products – do not look to fully capture the loan book return economics outlined earlier. This is unsurprising in the context of liquidity premiums implicit in such traded instruments, that aside such term debt or permanent capital is usually associated with more mature lending models. With the exception of securitized residuals, asset-backed bonds across senior and mezzanine capital structures, for instance, yield noticeably lower than the whole loan equivalents. Sub-investment grade lender bonds, commonly priced in the 7-9% area, are similar in that respect. Stocks in listed lenders have generally underperformed from a total return perspective in recent years, with loan book economics heavily outweighed by lender-specific event risks. All that said, we would note that certain risk assets related to specialist lending – such as high yield or securitized bonds – look cheap versus their traded peers.

Private market, illiquid alternatives such as whole loans (via marketplace platforms) and managed loan funds appear to better capture the return economics inherent in specialist loan books, in our view. Buying whole loans via marketplace platforms is an entirely new investing format, as is (largely) investing via loan funds. Marketplace whole loans can yield anywhere between 5% to upwards of 10%, depending on both credit risk categories and asset type, with consumer loans in the lower end and SME risk in the higher end, generally. (This simple observation ignores potential loss risks in such loans of course).

Managed funds investing in specialist credit markets comprise unlisted opportunity funds and selected listed investment trusts. Listed funds afford greater transparency of course in terms of asset profiles and underlying returns, with stock price action also a useful barometer for end-investor appetite for such strategies. In this respect price trends among some closed-end trusts have been stable as have dividend payouts (with above-market yields typically), however total returns in some others have been disappointing in recent years. Reasons for the out- or under-performance vary, but fundamentally reflects the sentiment of equity income investors who make up the bulk of the buyer base for such listed investment vehicles.

In theory at least, unlisted PE-style funds seem arguably best placed to provide diversified exposure into specialist lending sectors, in our view. Such funds have the benefit of being able to manage a mix of assets and exposures over the longer-term, without the burden of daily liquidity oversight (unlike listed loans funds). Conceptually at least, such vehicles are likely to be more nimble in exploiting debt and/ or equity value (optimizing the use of leverage either way) within the specialist lending markets in the UK, tapping ‘off-radar’ or bespoke opportunities away from the more mature and established types typically represented in the capital markets. But by the same token, we see alpha generation among such funds coming from the ability to source such ‘hard-to-access’ private opportunities, rather than asset selection per se. In-house capabilities to manage credit risk over the long-term would also be a key attribute, in our view.

Benchmarking returns to comparable investment types

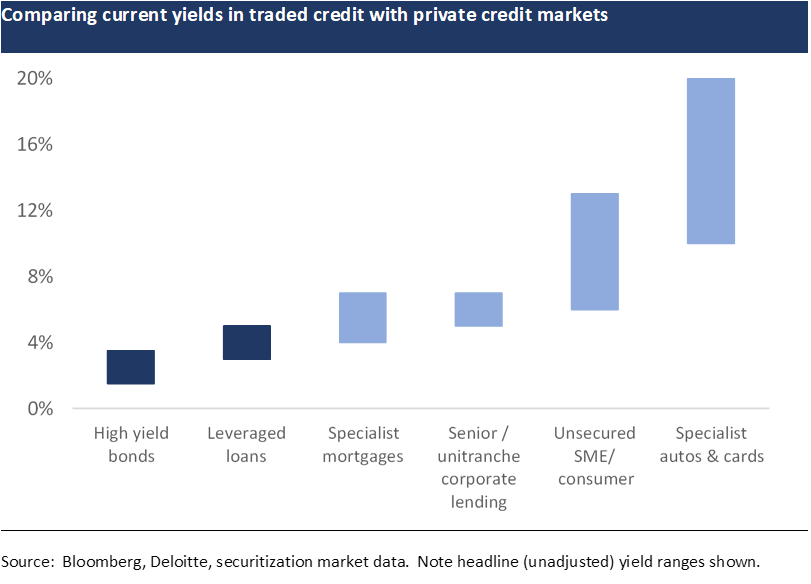

Total unlevered returns in the 4-6% range for mortgages and certainly the 10-15% range (or higher) for most other established specialist lending markets looks compelling of course versus most other comparable broadly traded markets, whether bonds (where HY benchmarks trade in the ca. 3% range) or corporate loans (par leverage loans ca. 4% currently). This yield basis to public markets has come to be a textbook mantra for private market investing, but of course overlooks the liquidity give-up in the latter opportunities.

Comparing specialist lending opportunities to other established private credit investing is a challenging exercise given the lack of returns data across unlisted funds in these markets. ‘Private credit’ investing has come to be associated with direct lending into mid-market or large cap corporates, typically via sponsored leveraged facilities. Based on available data from both Bloomberg and Preqin, we would surmise that funds invested in the vanilla end of such strategies (that is, excluding special situations or distressed, etc) have in the recent past generated total returns of approximately 6-9% annually. Looking through such fund returns into the underlying asset types, we would note that private senior or unitranche loans to corporates typically yield in the 5-7% area (source: Deloitte).

By the above yardsticks, specialist lending in the UK looks to generate superior yields and returns relative to the more ‘traditional’ form of private credit. Moreover, unlike direct lending in the corporate sectors where loan gearing and covenant protections have weakened in recent years, there is little evidence that there has been any meaningful slippage in underwritten credit quality within the specialist lending markets (indeed, if anything, certain high cost/ subprime markets have seen regulations limit aggressive lending practices). Part of the reason why there are better yield opportunities in specialist lending versus direct corporate lending is, in our view, the tighter supply of financing (or equally, lesser institutional penetration) coupled with a captive borrower audience in which demand is arguably more price inelastic. Private direct corporate lending, by contrast, is better characterised as being a borrower-friendly market currently, reflecting the heavy institutional inflows and lending deployments.

Potentially compelling risk-adjusted return opportunities certainly merits more prominence for UK specialist lending-related investments among institutional private credit strategies, a development that we see taking hold before long.

[Please contact us for more substantive intelligence into risk-return benchmarks in these markets, including insights into the manager universe]

Disclaimer

The information in this report is directed only at, and made available only to, persons who are deemed eligible counterparties, and/or professional or qualified institutional investors as defined by financial regulators including the Financial Conduct Authority. The material herein is not intended or suitable for retail clients.

The information and opinions contained in this report is to be used solely for informational purposes only, and should not be regarded as an offer, or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell a security, financial instrument or service discussed herein.

Integer Advisors LLP provides regulated investment advice and arranges or brings about deals in investments and makes arrangements with a view to transactions in investments and as such is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (the FCA) to carry out regulated activity under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA) as set out in in the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Regulated Activities Order) 2001 (RAO).

This report is not intended to be nor should the contents be construed as a financial promotion giving rise to an inducement to engage in investment activity. Integer Advisors are not acting as a fiduciary or an adviser and neither we nor any of our data providers or affiliates make any warranties, expressed or implied, as to the accuracy, adequacy, quality or fitness of the information or data for a particular purpose or use. Past performance is not a guide to future performance or returns and no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made regarding future performance or the value of any investments. All recipients of this report agree to never hold Integer Advisors responsible or liable for damages or otherwise arising from any decisions made whatsoever based on information or views available, inferred or expressed in this report.

Please see also our Legal Notice, Terms of Use and Privacy Policy on www.integer-advisors.com